Transfers at Undervalue Versus Corporate Attribution

Introduction

The Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) granted leave to John Aquino, 2304299 Ontario Inc., Marco Caruso, Giuseppe Anastasio a.k.a. Joe Ana and Lucia Coccia a.k.a. Lucia Canderle (“John Aquino et al.”) on January 19th, 2023 to appeal an Ontario Court of Appeal (“ONCA”) decision, Ernst & Young Inc v Aquino, 2022 ONCA 202, from March 10th, 2022. The appeal case, John Aquino, et al. v Ernst & Young, in its capacity as Court-Appointed Monitor of Bondfield Construction Company Limited, et al., concerns the doctrine of corporate attribution and transfers at undervalue in the context of the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act, RSC, 1985, c B-3 (“BIA”).

Facts

The main provision at the core of this case revolves around section 96 of the BIA. Section 96 contemplates the criteria for voidable transfers at undervalue. It reads:

“A court may declare that a transfer at undervalue is void as against, or, in Quebec, may not be set up against, the trustee – or order that a party to the transfer or any other person who is privy to the transfer, or all of those persons, pay to the estate the difference between the value of the consideration received by the debtor and the value of the consideration given by the debtor.”

Pursuant to section 96, courts can order parties to return certain transferred property if the value or consideration provided proves insufficient and the purpose of the transfer possesses an intent to defraud, defeat, or delay creditor(s). The case at bar involves Bondfield Construction Company Limited (“BCCL”) and Forma-Con Construction (“FCC”), BCCL’s affiliate. BCCL is one of Ontario’s largest public infrastructure construction corporations that participated in projects such as Toronto’s Union Station and St. Michael’s Hospital.

As a result of liquidity concerns commencing in 2015, BCCL and FCC hired Ernst & Young Inc (“EY”) to review the corporations’ financial turmoil. EY underscored that liquidity problems centred around cash flow. Acting on EY’s findings, BCCL’s creditors started to call loans.

BCCL and FCC eventually pursued restructuring vis-à-vis the Companies’ Creditors Arrangement Act, RSC, 1985, c C-36. EY, the appointed monitor and trustee, parsing BCCL and FCC’s financial reports, realized that BCCL deployed false invoices to illegitimately pay over $35,000,000 to non-arm’s length parties (FCC transferred over $11,000,000). These transfers succeeded under the authorization and supervision of John Aquino (BCCL and FCC’s president) and his associates.

Analysis

Do these transactions fall within the scope of transactions at undervalue pursuant to section 96? The ONCA seems to think so.

Section 96(1) of the BIA mandates that privies to the transfers at undervalue (in this case, BCCL and FCC) must cover the deficiency of the transaction at undervalue. Courts may also void these undervalued transfers.

John Aquino et al. put forth the argument that the transactions in question do not invoke section 96. In particular, they argue that because both BCCL and FCC were financially stable at the time of these transfers, these transfers did not render the debtor companies insolvent. Moreover, they articulate that an intention to defraud, defeat or delay creditors cannot be imputed to the debtor corporations. John Aquino et al. relied on Canadian Dredge & Dock Co v The Queen, [1985] 1 SCR 662 (“Canadian Dredge”), a landmark SCC case clarifying the doctrine of corporate attribution. This case specified that the doctrine does not apply if the fraudulent actions did not benefit the corporation. In light of these facts, John Aquino et al. claimed that section 96 does not capture these transfers.

Both the trial court and ONCA rightly adopted a more holistic analysis of section 96 to the facts. Firstly, Justice Dietrick of the Commercial List noted that the debtor companies’ financial statements outlining the financial health of BCCL and FCC were actually subject to litigation. Thus, these statements cannot be conclusively relied upon to establish the accuracy of the debtors’ true financial position. Second, badges of fraud can buttress the existence of an intent to defraud, defeat or delay creditors: e.g. unusual accounting practices, numerous transfers of exorbitant amounts, non-arm’s length relationship amongst the parties, among others. These badges lead to “a rebuttable presumption” to defraud, defeat or delay.

Agreeing with the trial court’s reasoning, ONCA held that the doctrine of corporate attribution, as outlined by the SCC in Canadian Dredge, requires special consideration in the BIA context. Writing for a unanimous ONCA, Justice Lauwers outlined three principles:

- Courts should be mindful of the legal context when prescribing intent

- Courts should be mindful of public policy and of the social purpose of holding corporations accountable for their actions

- Courts should be mindful of not applying the doctrine when it contravenes public interest.

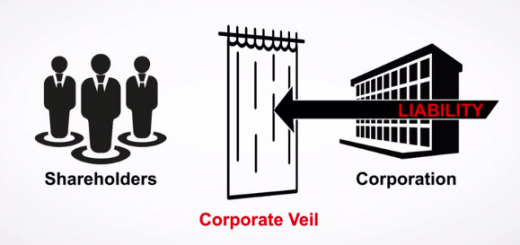

The ONCA argued that the application of the corporate attribution doctrine in the framework of the BIA should not favor fraudsters’ interests over those of creditors. In this case, BCCL and FCC’s illegitimate invoicing strategy harmed the interests of creditors. Even if Aquino et al. did not possess an intention to defraud the debtor corporations, they harmed legitimate claims of creditors. Ultimately, the fraudsters shoulder the liability to provide proper redress to innocent creditors.

Conclusion

This case highlights the influence of public policy concerns in the BIA framework. The ONCA turned toward social purpose justifications to prevent Aquino from benefitting at the expense of creditors, and, in the process, created a novel application of the doctrine of corporate attribution to impute Aquino’s intention to BCCL and FCC.

Canada’s bankruptcy regime has a central goal: fresh starts. This regime allows honest but unfortunate debtors to discharge debts and obtain a new chance at financial stability.

Via circumventing these goals vis-à-vis illegitimate, fraudulent invoicing practices, John Aquino et al. effectively undermined the integrity of the BIA structure. Professor Anna Lund of the University of Alberta’s faculty of law explains that section 96 of the BIA seeks to “claw back property that should be available to the creditor.” Creditors should not be deprived of their legal rights under the bankruptcy regime. Now, the cards are in the SCC’s hands to determine creditors’ proper redress. It is likely that the SCC will agree with the ONCA in heightening the role of public policy.

Join the conversation