To delay or not to delay? SCC ponders in Law Society of Saskatchewan v Abrametz

It is widely known that the Canadian court systems are generally plagued by delay for many reasons such as lack of resources, high volume of cases, etc. During COVID-19, it was observed that delay was further exacerbated due to lockdowns, which created additional barriers to access to justice. In contrast, administrative law and administrative decision-makers (“ADMs” or “ADM”) help ease the burden on the courts because they are known for more timely decision-making. However, it seems delay is creeping into administrative law.

In October 2000, the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) first addressed the issue of inordinate delay in Blencoe v British Columbia (Human Rights Commission), 2000 SCC 44 [Blencoe]. In a 5-to-4 split decision, the majority held inordinate delay, which does not affect hearing fairness, amounts to abuse of process if it meets the three-step test established in Blencoe and delay itself does not warrant a stay of proceeding for abuse of process.

Almost 22 years later, the SCC broke their silence on inordinate delay in Law Society of Saskatchewan v Abrametz, 2022 SCC 29 [Abrametz] to reaffirm Blencoe. In an 8-to-1 split decision, Justice Rowe writing for the majority, affirmed delay itself does not constitute an abuse of process nor does it justify a stay of proceedings in administrative law. In dissent, Justice Côté argued the majority conflates the test for abuse of process with the test for stay of proceedings. This creates a higher threshold for the affected party to receive a stay of proceedings, which “invites complacency in administrative proceedings” (Abrametz, para 136).

Facts of the Case

In 2012, the Law Society of Saskatchewan (“Law Society”) began an audit investigation against their member, Mr. Peter Abrametz, due to financial irregularities in his trust account. In 2015, the investigation concluded. The Law Society formally laid seven charges against Mr. Abrametz and they appointed a Hearing Committee (“Committee”) to oversee the disciplinary proceedings. In 2018, the Committee found Mr. Abrametz guilty on four of the seven charges. In early 2019, the Committee disbarred him for two years with readmission available thereafter.

Mr. Abrametz applied for a stay of proceedings to the Committee, arguing the Law Society’s lengthy investigation caused undue delay which amounted to an abuse of process. The Committee denied his application. He appealed to the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal (“SKCA”) which found there was inordinate delay and it resulted in significant prejudice against Mr. Abrametz “such that the public’s sense of decency and fairness would be affected and the Law Society’s disciplinary process brought into disrepute” (Abrametz, para 25). SKCA granted a stay of proceedings. The Law Society appealed to the SCC.

Issue

The SCC must answer whether inordinate delay that does not impact hearing fairness amounts to abuse of process in a disciplinary proceeding. To answer this, the SCC addressed the following sub-issues:

(i) What is the standard of review for issues of procedural fairness?

(ii) Did delay amount to abuse of process in Abrametz?

(iii) If so, is a stay of proceedings justified?

Vavilov Applies to Issues of Procedural Fairness Raised By Statutory Appeal

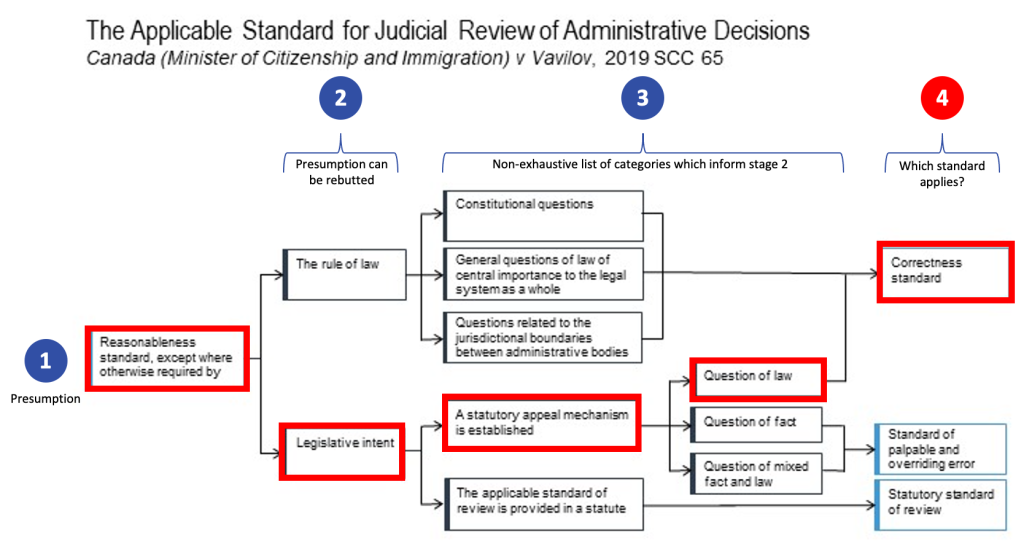

The standard of review (“SOR”) sets the foundation for the majority’s and dissent’s analyses in Abrametz. SOR determines how much deference (i.e., consideration) a reviewing court will give to an ADM when reviewing their decision. In Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65 [Vavilov], the SCC established a framework for determining the SOR when assessing the substance of an ADM’s decision. The SCC explicitly excluded issues of procedural fairness from Vavilov’s framework because procedural fairness review is distinct from substantive review (Vavilov, para 23). The former is concerned with the common law duty of fairness in the decision’s procedure and the latter is concerned with the decision’s substance or merits. Hence, they require different analyses.

Inordinate delay amounting to an abuse of process is a procedural fairness issue. The general rule from Mission Institution v. Khela, 2014 SCC 24 [Khela] is “the standard for determining whether the decision maker complied with the duty of procedural fairness will continue to be correctness” (Khela, para 79). This means the reviewing court will not defer to an ADM’s decision. Rather, it will conduct its own analysis on the issue and compare its outcome with the ADM’s outcome. If the outcomes match, then the ADM’s decision remains. If they do not match, then the ADM’s decision is quashed and the court’s decision remains.

In Abrametz, the majority applied the Vavilov framework of substantive review to procedural fairness review because the enabling statute in this case, Legal Profession Act, 1990, provided a statutory right of appeal. The presence of this mechanism had two implications: (i) the legislature intended to subject an ADM’s decision to judicial oversight; and (ii) the decision will be assessed as if it was an appeal of a lower court’s decision (i.e., appellate basis)(Vavilov, para 36). Since abuse of process is a question of law, the SOR is correctness (Abrametz, para 30).

Though both the majority and dissent arrive at the correctness standard, there is conflict in how they arrive there. Justice Côté argues that the correctness standard from Khela applies to Abrametz, regardless of the statutory appeal mechanism (Abrametz, para 129). In contrast, the majority justifies their application of Vavilov to Abrametz by arguing: (i) Abrametz was raised through appeal; and (ii) Khela was a judicial review case (not applicable here). While these considerations are valid, Justice Côté’s critique is also valid because Vavilov did not formally overturn Khela. In my opinion, the majority was biased towards Vavilov so they found a way to fit Abrametz in the Vavilov framework, which aligned with its goals of making the law on SOR “more certain, coherent, and workable going forward” (Vavilov, para 22).

Delay Did Not Amount to Abuse of Process

In Blencoe, the SCC recognized two categories of delay which constitute abuse of process. First, undue delay that impacts hearing fairness. This is when “memories have faded, essential witnesses are unavailable, or evidence has been lost” (Blencoe, para 102). Second, inordinate delay that does not impact hearing fairness, but causes significant prejudice (Blencoe, para 122 and 132). The present case falls in the second category.

In Abrametz, the majority applied the three-step test from Blencoe. In step one, the court must assess the overall context, including but not limited to, the following factors (Abrametz, para 51):

(i) the nature and purpose of the proceedings,

(ii) the length and causes of the delay, and

(iii) the complexity of the facts and issues in the case

In nature and purpose of the proceedings, the court noted disciplinary proceedings are sui generis (i.e., unique) in nature because their purpose is “…to protect the public, to regulate the profession, and to preserve public confidence in the profession (Abrametz, para 53-54). In length and causes of delay, the delay was 71 months long but the majority relied on the Committee’s finding that this delay was largely caused by Mr. Abrametz (14.5 months) due to his or his counsel’s unavailability, his application to temporarily stay the proceedings during the tax proceeding against him, and his complaint that the Law Society’s counsel was contributing to the delay (Abrametz, para 109). In complexity, the majority noted, the Committee was the fact-finder at first instance and SKCA owed them deference on the facts found. Since the SKCA replaced the Committee’s findings with their own, it meant the SKCA did not appreciate the complexity of this case. Thus, their replacement of facts was unjustified.

In step two, the delay must directly cause significant prejudice. Here, the majority was not convinced that the stress faced by Mr. Abrametz and his employees, the conditions placed on his practice, and the media attention amounted to “significant prejudice”. While Justice Rowe suggests the applicant may welcome delay because it enabled him to continue practicing, like Justice Côté, I strongly disagree with this point. This speculation presupposes that Mr. Abrametz was guilty before the hearing decision was rendered so he should continue practicing under conditions before he is stopped from doing so. Since steps one and two of the Blencoe test were not met, the court did not proceed to step three. Therefore, the majority did not find an abuse of process.

In contrast, Justice Côté applied the dissent’s test from Blencoe which takes a literal approach to inordinate delay. She found the delay was 32.5 months long and the Committee did not provide any inherent time requirements of a disciplinary proceeding. Here, the Committee missed a strong opportunity to present compelling data. From a simple Google search, I discovered each law society tracks hearing metrics, reports them annually to the Federation of Law Societies of Canada, who then drafts a National Discipline Standards report to show each law society’s progress (ex. 2014 and 2021). Justice Côté found this delay was “clearly unacceptable” and it impacted Mr. Abrametz by causing him stress, health-related concerns, and subjecting him to intrusive practice conditions (Abrametz, para 147).

It is worth noting that Justice Côté’s approach sets a lower threshold for future applicants to meet and potentially receive a stay of proceedings. A lower threshold raises policy concerns such as easy dismissal of serious disciplinary proceedings, complainants’ voices going unheard, and eroding the public’s trust in the administrative regime.

Stay of Proceedings Not Justified but Alternative Remedies Available

In Abrametz, the majority noted a stay order permanently dismisses the proceedings against the applicant in the disciplinary context (Abrametz, para 83). This means the charges will not be dealt with and the public may not be protected, which are serious public policy concerns. Thus, “a stay should be granted in the ‘clearest of cases’, when the abuse of process falls on the higher end” (Abrametz, para 83). When faced with an abuse of process proceeding, the court or tribunal must balance the public interests in asking: would going ahead with the proceeding result in more harm to the public interest than if the proceedings were permanently halted? (Abrametz, para 85). If yes, then a stay should be granted. If no, then the application for stay should be dismissed. In my view, Justice Côté rightfully observes that the majority conflates the test for abuse of process with the test for a stay. By outlining an additional consideration to determine if a stay order is warranted, the majority added a fourth-step to the Blencoe test. This indicates the majority is unwilling to grant access to the ultimate remedy, hence they raise the bar for the current and future applicants while balancing the public interest.

Since, the majority did not find an abuse of process, a stay of proceedings was not justified. Instead, they enumerated remedies alternative to a stay order. This indicates the majority’s intention for the parties to an administrative proceeding to be proactive. They even suggest a path for the party affected by delay to follow. First, the affected party should exhaust internal tribunal procedures, if any. If none, they should add their concerns to the record, essentially creating a paper trail. Second, they should seek a court order for an ADM to deal with a matter efficiently, if that is part of their statutory duty (i.e., mandamus). If the affected party has exhausted the alternative remedies, then they should seek a stay of proceedings.

Conclusion

In Abrametz, the majority and dissent have divergent views on the key issues in this case. In the end, the majority awarded costs against Mr. Abrametz while Justice Côté recommended quashing Mr. Abrametz’s penalty for disbarment. Although the majority provides compelling reasons for their position, their application of Vavilov to Abrametz was surprising. In an attempt to create certainty, they created uncertainty for determining the SOR on issues of procedural fairness. Presently, there is insufficient data on the application of Abrametz because it is a fairly recent decision, however, this case may be the first nail in the coffin for overturning Khela.

Join the conversation