July 26, 2016

This article was co-written by Richard Haigh and Victoria Peter. Part I is found here.

Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin is now the longest serving chief justice in Canadian history, having held the title of Chief since January 2000 and the title of longest serving since September of 2013 (when she sailed past Sir William Ritchie’s 13 ¾ years). More astounding still is that after 16 years at the helm, she shows no signs of slowing down, and looks set, two years from now, to reach 75 years of age – unfortunately, due to the mandatory retirement age, she won’t reach the magic number of 20 years as Chief).

We thought it timely, therefore, to assess her entire output as chief justice, so we’ve examined all the cases in which she’s named as C.J., beginning with the twin decisions handed down on January 20, 2000, Lindsay v. Saskatchewan (Worker’s Compensation Board) and Kovach v. B.C. (Worker’s Compensation Board) and ending with the December 17, 2015 decision in CIBC v. Green (our analysis is done on an annual basis, so we excluded 2016 decisions).

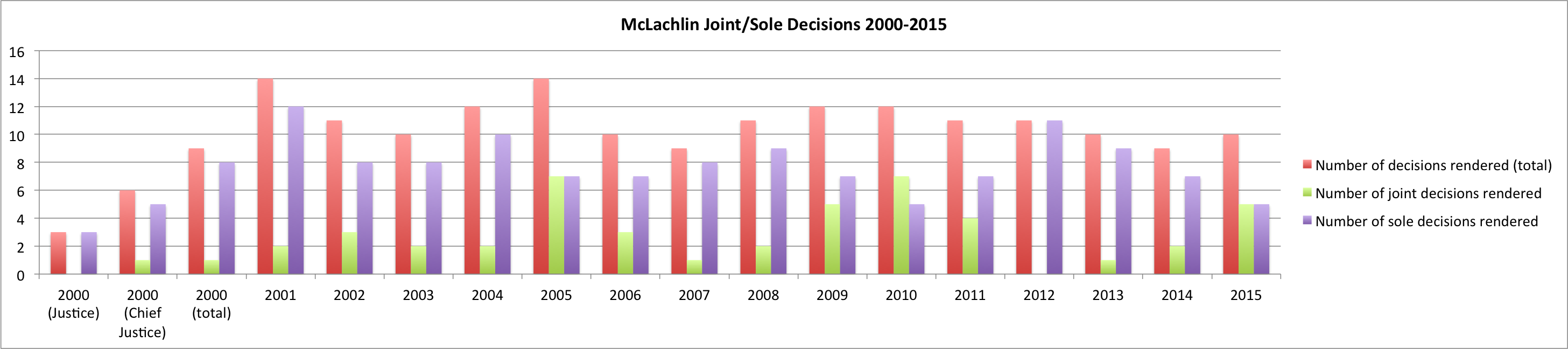

Sole vs. Joint Decisions: The tables below show, annually, McLachlin’s sole and joint decisions and the judges she has teamed up. As the purple bar indicates, McLachlin writes more frequently solo opinions, although there have been a few years where this is not the case: in 2010, for example, more of her decisions were joint than sole (58% vs. 42%); in 2005 and 2015, she was almost perfectly balanced; and in 2009, 42% were joint. By and large, however, in most years she renders significantly more judgments alone: the high point occurring in 2012 when all of her decisions were sole opinions. We are unsure of what to make of any of this. Is she a loner? Does she have such a strong presence on the Court, that others simply agree with her? Does she like writing? Is she a workaholic? There’s probably some truth in all of this.

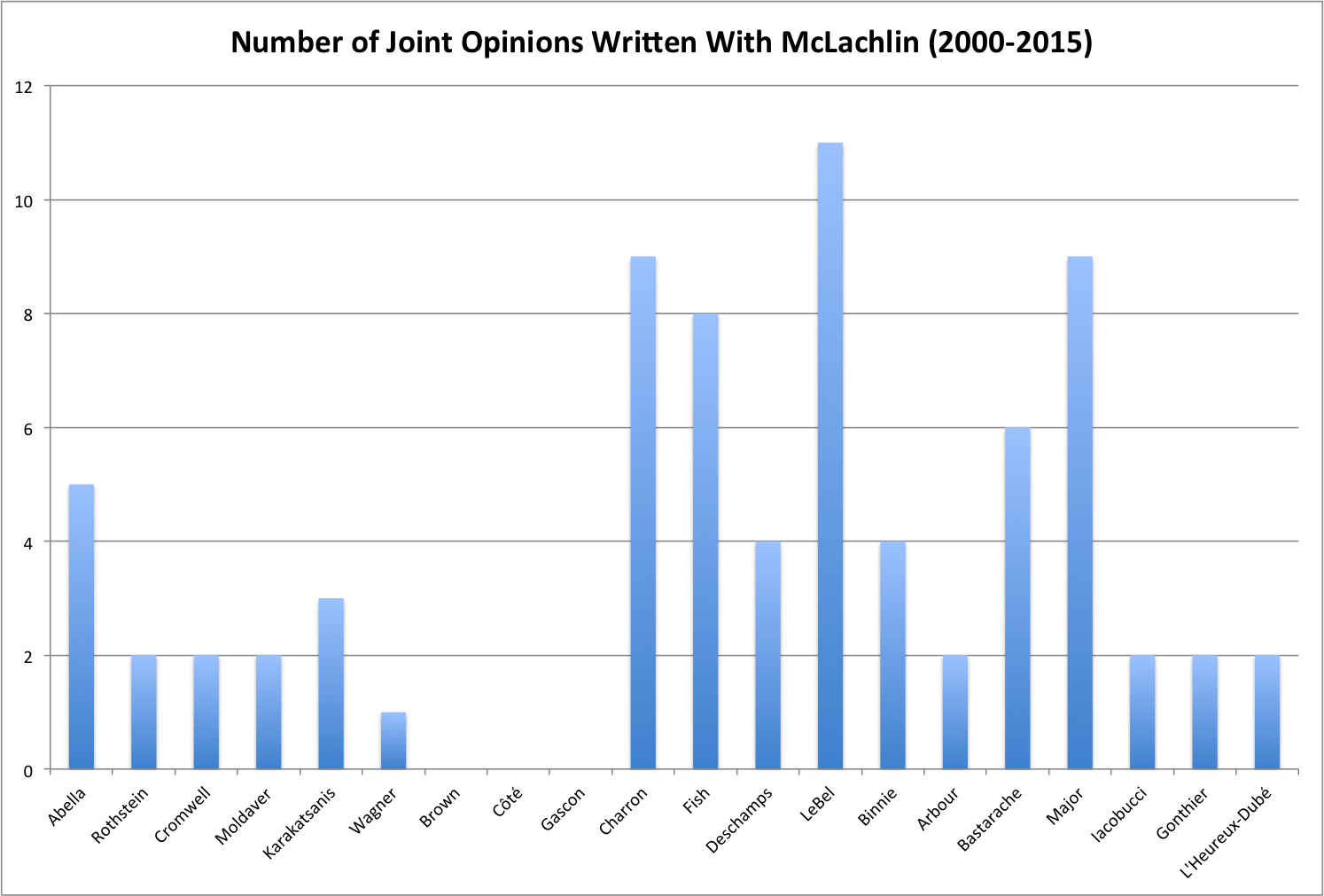

Moreover, when she does collaborate, she seems to prefer signing on with some colleagues (Justices LeBel, Charron, Fish, Major and Bastarache) over others (although Justices Rothstein, Binnie, Deschamps and Abella have been together on the Court with McLachlin for a similar amount of time to Fish and Charron, they have far fewer joint decisions with her; Justice LeBel, on the other hand, has spent the most time with her – over 14 years – so it is less surprising that he is at the top.) Put differently, if we take Charron’s 6.8 years spent together with MacLachlin, she penned about 1.29 judgments per year with her, whereas at the other end, Rothstein at 0.21, Cromwell at 0.0.29 and Wagner at 0.30 have the lowest rate of joint authorship. She has written no joint opinions with Brown, Côté and Gascon (which makes sense since they're relatively new to the bench). (Also, note that these figures may be somewhat inflated since we include opinions where the entire court or the court minus one decided to jointly author a decision (for example, Reference re Supreme Court Act, ss 5 and 6 (2015) and Mugasera v. Canada (Min of Citizenship and Immigration (2005)).)

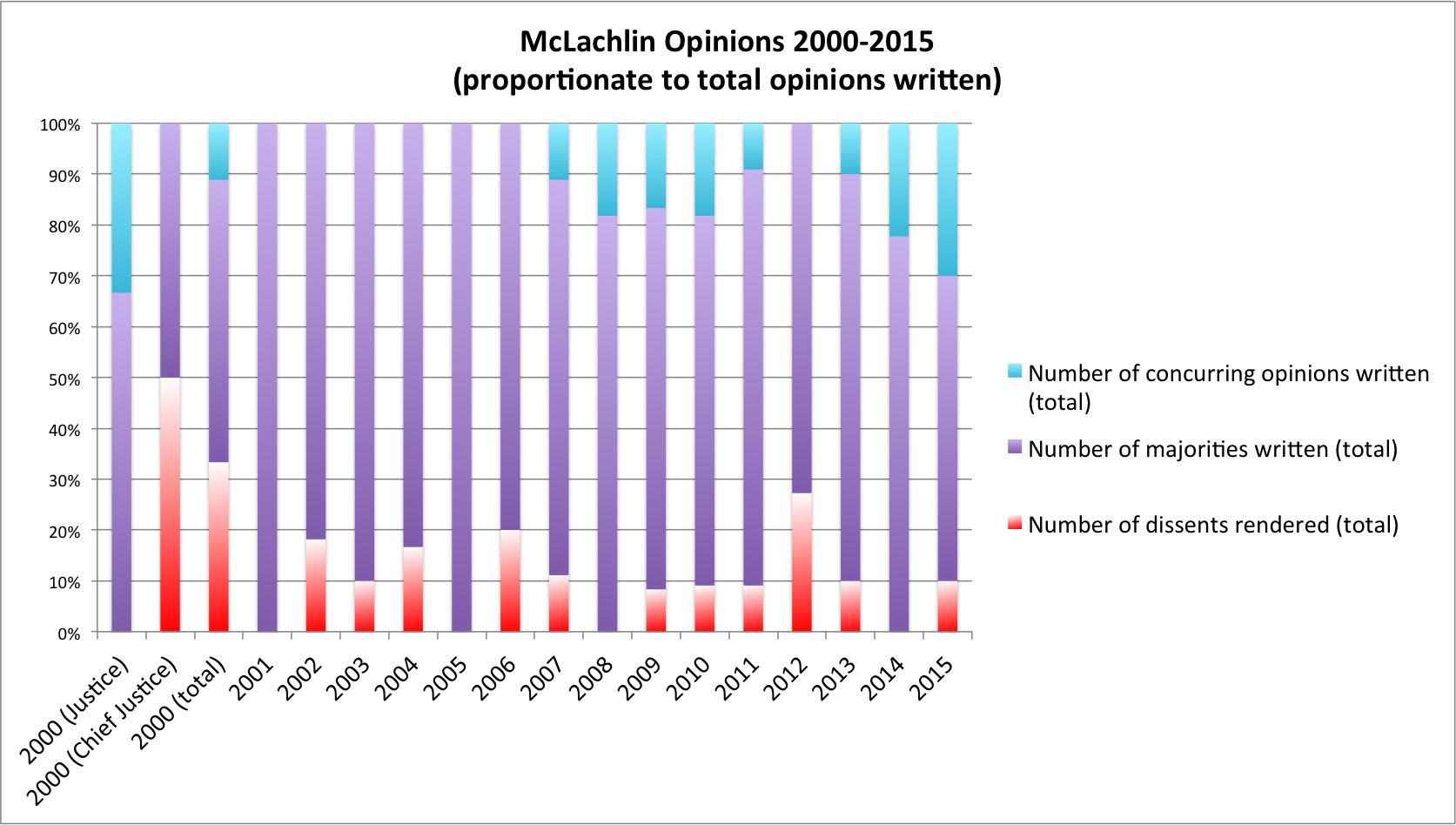

Majority-Concurring-Dissent Decisions: The chart below shows the breakdown of judgments by majority, concurrence or dissent. Beginning in 2007, McLachlin, as Chief Justice, begins to write the occasional concurring opinion. There is a general impression, at least currently, that McLachlin is a consensus-seeking judge. That she did not write any separate concurring opinions as Chief Justice until seven years into her tenure is testament to this fact. It could be pointed out that the chart appears to show a trend towards an increasing number of concurring decisions – which might run counter to the impression – but it should be noted that the chart expresses data as a proportion of her total decisions rendered, and the numbers each year are relatively small. Thus, while she wrote three concurring opinions in 2015, this is only one more than in 2014 – that is, the chart accentuates the differences somewhat. Of all the years since becoming Chief, 2012 is probably the most exceptional year in that McLachlin did not write any concurring opinions, but wrote three dissents (as Chief Justice, her largest number of dissents since the year 2000). But overall, her legacy mainly is one of few dissents and concurrences, and a much larger percentage of majority opinions.

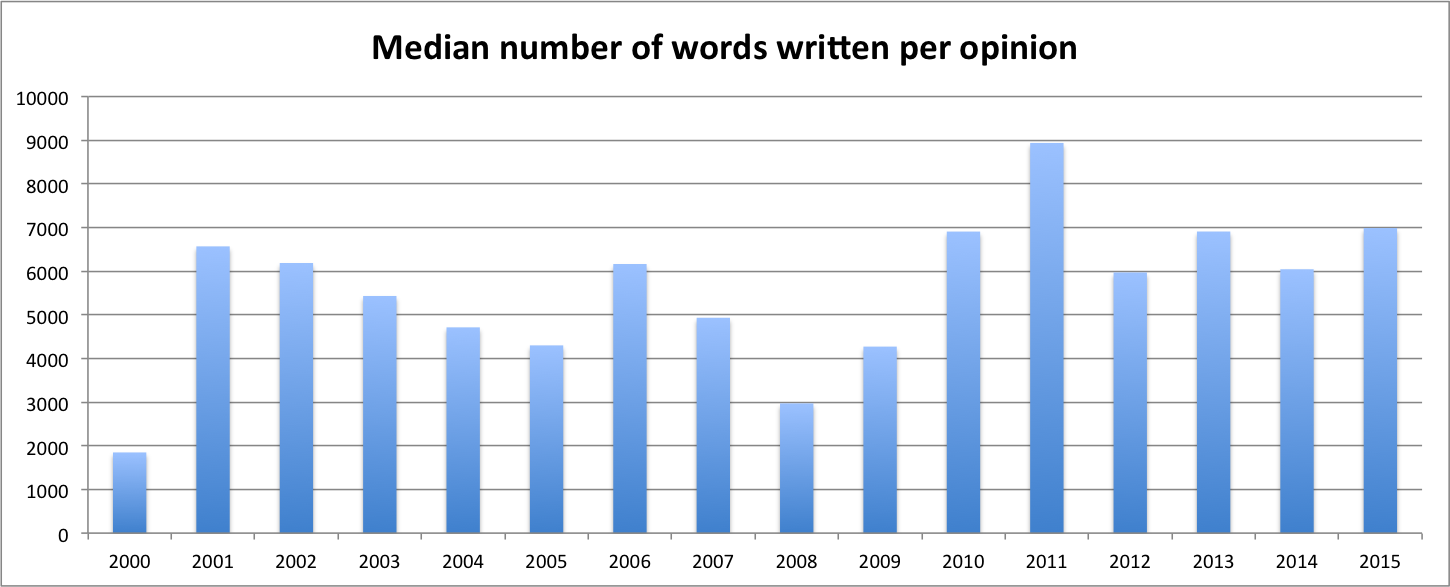

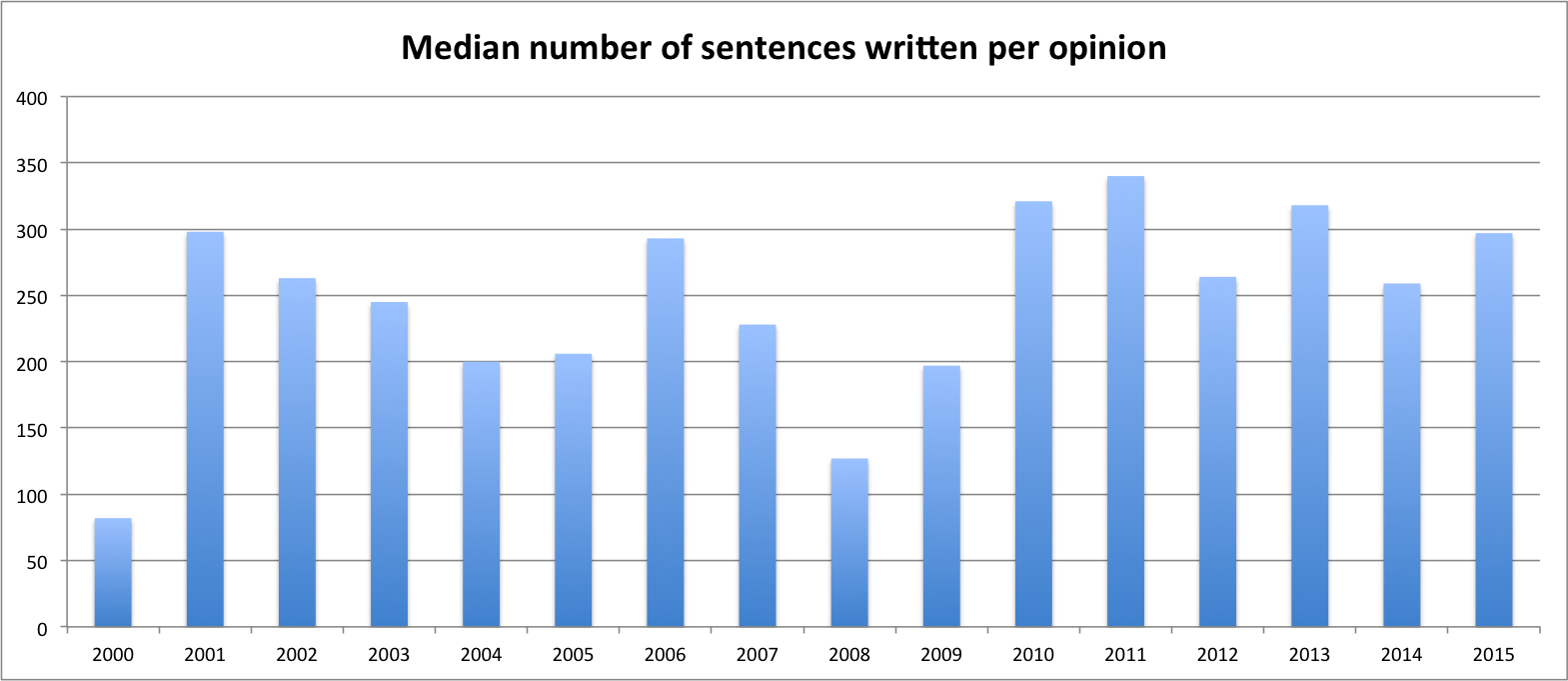

Word and Sentence Counts: These are based on sole decisions only; the two charts below show median word and sentence counts from 2000 to 2015. Given our findings in our blog of April 7, 2016, there isn’t anything terribly unusual here. Notice how the two charts are visually similar – put in another way, her sentence construction, at least in terms of length, remains relatively consistent throughout her time as Chief. Two observations: firstly, in 2000, her first year as Chief Justice, her judgments were much shorter. It is not all that clear as to why: is it a coincidence that the only year in which she rendered no dissents nor did she concur with anyone is also the year in which her judgments were the most concise? Or is it that a new Chief Justice is somewhat overawed by her position, and spends less time writing, more time gaining knowledge about running the Court? Or something else entirely? Further research is required.

Second, there are a couple of outlier years where she seems to write less and more: in 2000 and 2008 her median output is under 3000 words per opinion; in 2011, her median output was almost 9000. Compare those to almost any other year where the opinions fall generally within the 4000-6000 word range. The most likely reasons for this is simply complexity of cases (or what almost amounts to the same thing, the desire to render difficult philosophical concepts into legal rights) – for example, in 2011, Canada (A.G.) v. P.H.S. Community Services Society took well over 14,000 words to determine whether a federal law that has a regulatory effect on provincial health was a valid exercise of the federal criminal power, whether interjurisdictional immunity could apply to a provincial scheme, whether s.7 of the Charter was offended where a government minister failed to extend an exemption from criminal laws, and if so, whether s. 1 could save such refusal. In contast, the most complex case in 2008 involved a question related to the judge’s charge to the jury and whether issue estoppel should apply in criminal cases – not quite the dense political and philosophical areas of law found in groundbreaking constitutional and Charter cases.

In sum, McLachlin’s output is worthy of a Chief Justice who has spent many years on the Court. She continues to produce a remarkable number of opinions annually, while attending to her other duties as Chief, she is squarely in the majority camp for most decisions, and is also able to join with all of her colleagues, albeit some more frequently than others. In order to see how her legacy compares with her peers, our next project will be to compare and contrast Chief Justice Maclachlin’s output with her two Charter-era predecessors: Chief Justice Brian Dickson and Antonio Lamer.