SCC to Determine Constitutionality of Administrative Segregation

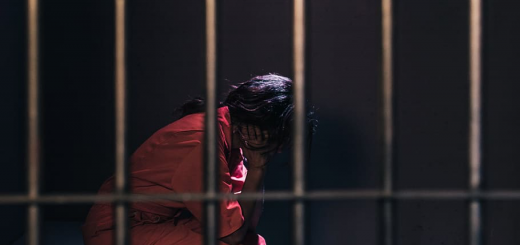

In February, the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) granted leave for two appeals, Attorney General of Canada v Corporation of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association (SCC Case Number 38574), and Attorney General of Canada v British Columbia Civil Liberties Association (SCC Case Number 38814). These two cases, which the SCC will hear together, deal with the constitutionality of administrative segregation—also known as solitary confinement—in Canadian prisons, and will determine the future of this practice in Canada.

Both the Ontario-based Canadian Civil Liberties Association (“CCLA”) and the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association (“BCCLA”) brought challenges in their respective provinces to the practice of administrative segregation. Both cases were appealed to their provincial courts of appeal. Though deciding the cases on different grounds, both appeal courts ultimately ruled the current administrative segregation regime unconstitutional, particularly as it authorizes administrative segregation for periods exceeding 15 days—a limit recommended by the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, UNGAOR, 70th Sess, UN Doc/A/Res/70/175 (17 December 2015).

Ontario Court of Appeal (“ONCA”) Decision

In Canadian Civil Liberties Association v Canada (Attorney General), 2019 ONCA 243 [CCLA 2019], the CCLA argued that sections 31-37 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, SC 1992, c 20 [CCRA], which authorize administrative segregation, violate ss. 7, 11(h), and 12 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms [Charter] (CCLA 2019, para 3). The CCLA sought a declaration that administrative segregation should be banned entirely for inmates aged 18-21, inmates with mental illnesses, or inmates placed in administrative segregation for their own protection, and sought a general limit of 15 days for all inmates (CCLA 2019, para 3).

Under s. 12, they argued that administrative segregation constitutes cruel and unusual punishment for young adults, because it has detrimental effects on their brain development, and for inmates with mental illnesses, because they are “particularly vulnerable to harm from administrative segregation” (CCLA 2019, para 31). They also argued that putting any inmate in administrative segregation for more than 15 days violates s. 12 because “prolonged segregation poses a serious risk of negative psychological effects” (CCLA 2019, para 31). Further, under s. 11(h), they argued that “the practice of segregating inmates for their own protection amounts to an additional form of punishment, contrary to the prohibition against double jeopardy enshrined in s. 11(h) of the Charter” (CCLA 2019, para 32). Finally, under s. 7, they argued that the relevant provisions of the CCRA infringe inmates’ rights to liberty and security of the person in a grossly disproportionate way, and in an arbitrary and procedurally unfair manner, given the lack of independent oversight (CCLA 2019, para 33).

Justice Benotto, in a unanimous decision, held that the s. 12 argument was “the determinative issue on this appeal” (CCLA 2019, para 55). She concluded that administrative segregation of young adults and of inmates with mental illnesses was not a s. 12 violation but agreed with the CCLA that putting any inmates in administrative segregation for longer than 15 days is a cruel and unusual punishment under s. 12. For young adult inmates, she deferred to the application judge’s conclusion that there was no evidence of termination of brain development before 15 days in young adults; therefore, she held that administrative segregation up to the 15-day general limit is not a cruel and unusual punishment for young adults, as it does not impact brain development in the manner the CCLA asserted (CCLA 2019, para 61). For inmates with mental illnesses, she concluded that there was insufficient evidence before the court to find the practice a violation of s. 12. She wrote:

In principle, I agree with the CCLA that those with mental illness should not be placed in administrative segregation. However, the evidence does not provide the court with a meaningful way to identify those inmates whose particular mental illnesses are of such a kind as to render administrative segregation for any length of time cruel and unusual. I take some comfort in my view that a cap of 15 days would reduce the risk of harm to inmates who suffer from mental illness – at least until the court has the benefit of medical and institutional expert evidence to address meaningful guidelines. This issue therefore remains to be determined another day (CCLA 2019, para 66).

Unlike with these first two arguments, Justice Benotto disagreed with the application judge concerning the CCLA’s s. 12 argument for administrative segregation lasting longer than 15 days. The application judge determined that the current legislative scheme was sufficient, because it required the monitoring of inmates, and s. 87(a) required that inmates’ physical and mental health be taken into consideration in making decisions about administrative segregation (CCLA 2019, para 70). Justice Benotto, however, concluded that the evidence showed that this monitoring of inmates “only detects harm once it has already occurred—it does not predict or prevent it,” which fails to insulate against a s. 12 violation (CCLA 2019, para 71). Given the ample evidence that “prolonged administrative segregation causes foreseeable and expected harm,” and that the legislative safeguards like the monitoring process were not sufficient to prevent this harm, she determined that the provisions of CCRA authorizing administrative segregation for longer than 15 days violated s. 12 of the Charter (CCLA 2019, para 69, 119). This violation, she concluded, was not justified under s. 1 of the Charter, as the administrative segregation scheme did not “minimally impair the s. 12 rights of inmates,” but “expose[d] the inmates to the risk of severe and potentially permanent psychological harm” (CCLA 2019, para 126).

After finding prolonged administrative segregation unconstitutional under s. 12, Justice Benotto only briefly considered the CCLA’s ss. 11(h) and s. 7 arguments. She deferred to the application judge’s conclusion that segregating inmates for their own protection did not violate s. 11(h), because it did not prolong inmate sentences, was not imposed for the purpose of sentencing, and was not a sanction under the Criminal Code (CCLA 2019, para 135). Similarly, she agreed with the application judge’s finding under s. 7 about inmates with mental illness and young adult inmates. The application judge held that since administrative segregation in these contexts was not found to violate s. 12, they did not violate s. 7, as precedent established that s. 7 “cannot find a treatment or punishment disproportionate where it passes the test under section 12” (CCLA v Canada, 2017 ONSC 7491 at para 267).

British Columbia Court of Appeal (“BCCA”) Decision

In British Columbia Civil Liberties Association v Canada (Attorney General), 2019 BCCA 228 [BCCLA 2019], the BCCLA advanced slightly different arguments than the CCLA, bringing ss. 9, 10, and 15 arguments, in addition to the arguments under ss. 7 and 12 of the Charter. At trial, the BCCLA was far more successful than the CCLA. The trial judge found the relevant provisions of the CCRA to be a violation of s. 7 of the Charter, particularly in authorizing administrative segregation of inmates over 15 days, and s. 15, on the basis that they discriminate against mentally ill, disabled, and Indigenous inmates (BCCLA 2019, paras 15, 17–18). The BCCA decision, however, overturned some of these findings. Although it upheld the s. 7 violation, it found that there was no violation of s. 15 warranting a declaration of invalidity of the legislative scheme.

Under s. 7, the BCCA agreed with the trial judge that the relevant sections of the CCRA violated the liberty and security of the person in an overbroad and grossly disproportionate manner. Justice Fitch concluded that “prolonged and indefinite segregation inflicts harm on inmates subject to it and ultimately undermines the goal of institutional security,” making the provisions overbroad (BCCLA 2019, para 165). Similarly, he held that “the draconian impact of the law on segregated inmates…is so grossly disproportionate to the objectives of the provision that it offends the fundamental norms of a free and democratic society” (BCCLA 2019, para 167).

Justice Fitch also addressed the procedural fairness arguments under s. 7. On appeal, the Attorney General had conceded that the legislation was procedurally unfair insofar as it required internal review of the decision to segregate inmates (BCCLA 2019, para 173). The BCCA agreed and held that procedural fairness mandates “the external review of administrative segregation decisions by reviewers who are independent of [Correctional Services Canada (“CSC”)]” (BCCLA 2019, para 192). Further, he agreed with the trial judge that inmates should have the right to counsel at administrative segregation review hearings (BCCLA 2019, para 206). However, he determined that it was “not necessary to strike down the legislation on this account” (BCCLA 2019, para 208).

Finally, in addressing the s. 15 arguments, Justice Fitch set aside the trial judge’s declaration of invalidity. Regarding the argument that the provisions discriminate against Indigenous inmates, he concluded that the trial judge did not identify which provisions infringe the s. 15 rights of Indigenous inmates, and did not discuss how the relevant provisions in purpose or in effect infringe s. 15. He held that “[w]hile the judge identifies organizational failings on the part of CSC in following its guiding principles and policies in resorting to administrative segregation for Indigenous offenders, these failings are not sourced in the legislation itself” (BCCLA 2019, para 214). Because the issue is rooted in “the maladministration of the legislative regime by CSC staff,” rather than the legislation itself, the BCCA concluded that a declaration of invalidity was an inappropriate remedy.

The BCCA also addressed the s. 15 argument about discrimination against mentally ill and disabled inmates. Justice Fitch noted that the phrase “mentally ill and/or disabled” is imprecise, and the trial judge’s decision “provides no guidance to the legislature on where the line should be drawn between inmates who are mentally ill and/or disabled and those who are not” (BCCLA 2019, para 228). The ONCA decision, released prior to the BCCA decision, similarly held that there was insufficient evidence of how to precisely identify which inmates had mental illnesses that would make administrative segregation a cruel and unusual punishment; Justice Fitch noted that this provided additional support for “[t]he practical difficulties associatied with the exercise of line-drawing in this context (BCCLA 2019, para 229). Like Justice Benotto, Justice Fitch pointed to the provisions of the CCRA which “require individualized assessment of whether an inmate’s mental health needs are such as to preclude resort to administrative segregation” to suggest that the administrative segregation regime satisfactorily addresses the potential harm to mentally ill inmates, and thus does not violate s. 15 (BCCLA 2019, para 236).

Ultimately, the BCCA upheld the trial judge’s decision that the relevant provisions of the CCRA violated s. 7 of the Charter. However, Justice Fitch determined that the appropriate remedy for the problems identified in relation to s. 15 of the Charter was not a declaration of invalidity but declaratory relief aimed at changing the way CSC conducts administrative segregation (BCCLA 2019, paras 265, 267). Consequently, he made a declaration that CSC breached its obligation under the CCRA to “give meaningful consideration to the health care needs of mentally ill and/or disabled inmates before placing or confirming the placement of such inmates in administrative segregation,” and to ensure that “inmates placed in administrative segregation are given a reasonable opportunity to retain and instruct counsel without delay” (BCCLA 2019, paras 269–270). He declined to make a specific declaration relating to Indigenous inmates, as he argued that none of the parties had identified how CSC has “discriminated against Indigenous inmates or otherwise breached its statutory obligations in relation to indigenous inmates,” so “any declaration this Court could grant would necessarily be vague” and “would not assist CSC in devising remedial measures” (BCCLA 2019, para 272).

Future SCC Appeal

The SCC will hear these cases together, and will have the opportunity to determine whether, and to what extent, administrative segregation in Canada is a violation of Charter rights.

Given that the BCCA and the ONCA agreed that prolonged administrative segregation was unconstitutional, it seems likely that the SCC will make a similar finding and uphold the decision of both courts of appeal. However, prolonged administrative segregation was declared unconstitutional under s. 12 in Ontario, and under s. 7 in BC. It remains to be seen whether the SCC will favour the s. 7 or s. 12 arguments in making their decision.

Similarly, it will be interesting to see how the SCC treats the s. 7 arguments overall, as the ONCA and BCCA judges came to quite different conclusions about the applicability of s. 7. The ONCA judge largely dismissed the CCLA’s s. 7 arguments, while the BCCA used s. 7 as the determinative factor in finding the legislative scheme unconstitutional. The SCC will need to reconcile these significant differences in addressing the s. 7 arguments.

Finally, the SCC appeal provides a second opportunity for an appeal court to consider the s. 15 arguments made by the BCCLA, as the CCLA did not advance a s. 15 argument in their submissions. Beyond simply weighing in on the substantive question of whether equality rights of Indigenous or mentally ill inmates were violated through the administrative segregation regime, these appeals will also require the SCC to consider what the appropriate form of relief is, and whether, like the BCCA concluded, declaratory relief is more appropriate than a declaration of invalidity and the mandatory legislative change that requires. There may not have been sufficient time since the BCCA’s declaration to assess whether such declaratory relief actually produced tangible change in CSC’s administrative segregation practices. Regardless, it will provide an opportunity for the SCC to comment on how to best reform the administrative segregation scheme so that it is constitutionally compliant—whether that requires rebuking CSC in how administrative segregation is carried out, rewriting the governing legislation, or issuing general or context-specific prohibitions on its use.

Join the conversation