Private Health Care Still an Uphill Battle: A Step Backward in Cambie Surgeries Corporation v. British Columbia (Medical Services Commission)

The battle for private health care in Canada has hit another roadblock after the BC Court of Appeal’s recent judgment in Cambie Surgeries Corporation v. British Columbia (Medical Services Commission), 2010 BCCA 396. Groberman J., writing for an unanimous Court, held that the Medical Services Commission (“Commission”) of British Columbia is entitled to audit private companies providing medical care. However, at the same time, Groberman J. also ruled that a previously-issued injunction requiring the private company to cooperate with auditors was incorrectly issued.

Background and Facts

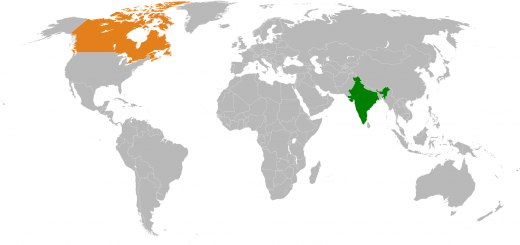

Many Canadians are unclear on the current state of the law concerning the grey line which divides public and private health care. It should come as no surprise that one of the great defining characteristics of Canada which sets us apart from our neighbour to the south is the availability of universal basic health insurance. These schemes are administered by the provincial governments through governing statutes. In British Columbia, the relevant legislation is the Medicare Protection Act, R.S.B.C. 1996, c. 286.

Through the allowance of direct billing from physician to patient, the statute somewhat allows what I term “pseudo-private health care.” The relevant provisions of the Medicare Protection Act are outlined below.

17 (1) Except as specified in this Act or the regulations or by the commission under this Act, a person must not charge a beneficiary

(a) for a benefit, or

(b) for materials, consultations, procedures, use of an office, clinic or other place or for any other matters that relate to the rendering of a benefit.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply

…(c) if the service was rendered by a practitioner who

(i) has made an election under section 14 (1) … [which allows for physicians to opt-out]

18 (1) If a medical practitioner who is not enrolled renders a service to a beneficiary and the service would be a benefit if rendered by an enrolled medical practitioner, a person must not charge the beneficiary for, or in relation to, the service an amount that, in total, is greater than

(a) the amount that would be payable under this Act, by the commission, for the service if rendered by an enrolled medical practitioner ….

The scheme, then, has the effect of allowing doctors to bill patients directly, but at a rate no higher than the medical services would be valued within the public healthcare system. It for this reason I dub the scheme “pseudo-private healthcare.”

Show Me The Money!

Cambie Surgeries Corp., a company which established a Vancouver private hospital called Cambie Surgery Centre, were accused of extra billing which ultimately brought the company into the Commission’s crosshairs. Instead of denying these allegations, the clinics admitted to extra billing, but claimed that (a) patients had signed acknowledgement forms agreeing to the practice and (b) the aforementioned prohibitions in the Medicare Protection Act are unconstitutional.

In November 2009, the Commission successfully argued an interlocutory application where the government sought injunctive relief to allow its inspectors to enter the clinics and audit confidential medical records. The chambers judge granted the injunction allowing the auditors to inspect the clinics, primarily on the basis that the relief sought was final, as the injunction would act as a summary determination of the issue. She then applied a modified RJR-Macdonald test (set down in RJR-MacDonald v. Canada (AG), [1994] 1 SCR 311) to determine when a final injunction may be ordered.

This test requires: (1) the applicant to demonstrate there is a serious question to be tried, (2) the applicant to show that it may suffer irreparable harm if the relief is not granted and (3) the court to determine whether the balance of convenience favours the applicant or the respondent. The test is modified in cases where the relief sought is final by requiring the court to conduct an “extensive review of the merits [on the first point], with the anticipated results on the merits also being kept in mind at the second and third stages of the test.”

So, What’s The Problem?

On appeal, Cambie Surgeries contended that the judge erred in not considering the constitutionality of the impugned legislation at the first stage of the RJR-MacDonald test. Conversely, the Commission argued the judge was not required to reach a conclusion on constitutionality because the Commission has a right to perform an audit irrespective of whether a violation has (or has not) occurred with respect to ss. 17 and 18 of the Medicare Protection Act.

Groberman J. accepted the position of the Commission, but went even further and determined that the Chambers judge had incorrectly set out the test for the granting of an injunction for final relief. In coming to this conclusion, he cited RJR-MacDonald, which states that “when the result of the interlocutionary motion will in effect amount to a final determination of an action….” Then, according to Groberman J., the test the Chambers judge used was incorrect as it misapplied RJR-MacDonald, which is only available for interlocutionary relief (not final relief). As stated in RJR-MacDonald, the modified test is not available for actions seeking final relief, but for a very specific, special class of interlocutionary motions where an injunction would merely have a final effect in bringing litigation to an end.

The test in RJR-MacDonald for a final determination is different. A party is instead required to establish legal rights. After those rights have been established, the court is required to determine whether an injunction is an appropriate remedy.

Groberman J. found the Commission was legally entitled to conduct an audit under s. 36 of the Medicare Protection Act. However, he also established that an injunction was inappropriate given that the statute provided a clear and adequate statutory provision allowing an audit.

This case is interesting as it can be viewed from two perspectives: first, that Cambie Surgeries emerged victorious as a result of the injunction being overturned, and second, that the BC government also succeeded in “winning” the right to audit private clinics. Regardless of what viewpoint one adopts, I find the value of this case to be in the far-reaching implications this decision, and related decisions will have on private health care in any Canadian province. While allowing the audit today may displease proponents of a two-tiered system, a more interesting decision is yet to come. At the time of posting, Cambie Surgeries is still involved in litigation launched in 2008 alleging ss. 17 and 18 of the Medicare Protection Act violate a Charter right to patient freedoms. It is too early to speculate on the outcome, but the landscape of Canadian health care could significantly change in the not-so-distant future.

Join the conversation