Live From the SCC: Ktunaxa Nation v Minister of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations

The Supreme Court of Canada heard arguments on December 1st about whether section 2a of the Charter – the provision that protects religious freedom in our country—could be extended to include an Aboriginal spiritual connection to land. This is the first time the Supreme Court will consider an Aboriginal religious freedom claim under the Charter. You can watch the live webcast here.

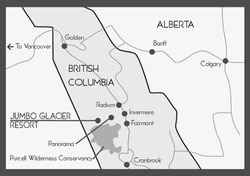

The facts, in brief, are as follows: Glacier Resorts want to build a ski resort on a plot of Crown land. The Ktunaxa Nation claim that they have a spiritual connection to this plot of land (which they call Qat’muk), and that building a ski resort there would destroy that spiritual connection. The Minister of Forests, Lands, & Natural Resources approved Glacier Resorts’ proposal to build the ski resort. The Minister considered the Ktunaxa’s right to religious practices under section 35 of the Constitution, but there was some doubt as to whether the Minister properly considered the Ktunaxa’s section 2a right to religious freedom in our Charter. The Ktunaxa appealed the Minister’s decision. They lost at trial and on appeal to the British Columbia Court of Appeal.

I have already written about the British Columbia Court of Appeal decision here. In that article, I argued that the BCCA judge’s decision to dismiss the Ktunaxa freedom of religion claim (by excluding such a claim to sacred land from the initial scope of section 2a) was wrong for two reasons:

- The holding is doctrinally inconsistent with section 2a jurisprudence, which has been built upon an expansive interpretation of religious claims, limiting them only after allowing the claim in through section 1 of the Charter; and,

- The holding is problematic for policy reasons: it does not consider the unique nature of Aboriginal spirituality and its connection to land, and, by ignoring this unique nature, essentially excludes Aboriginal spirituality as a religious claim from Charter protection.

This Charter question has been framed before the Supreme Court in the following way: should section 2a of the Charter allow in religious claims that seek protection for sacred land and/or religious claims that may infringe on the rights of others (i.e. developers building on Crown land)?

There are three additional issues before the SCC:

- How section 35’s protection of Aboriginal rights should interact with section 2a’s protection of religious freedom where both sections are engaged;

- Whether the Crown’s consultation in this case was adequate; and

- How the standard of review (correctness or reasonableness) should be applied in this case.

All nine judges—including the new appointee, Justice Rowe—were in attendance.

The Argument of the Appellants (Ktunaxa Nation)

Peter R Grant, counsel for the Appellant, opened with a number of historical examples of Aboriginal people being forced to choose between those rights protected under the Charter (like the right to vote) or keeping their Indian status. Grant posited that this case is similarly about Aboriginal people being told by the government that their religious practices are less worthy of Charter protection than other Canadians.

The Appellants’ position on the Charter issue was that the lower courts incorrectly put internal limits on section 2a (by saying that section 2a did not protect a right like this one), instead of allowing the claim within 2a and then weighing the different values at stake under a proportionality analysis.

The Appellants argued that where a right to religious freedom under section 2a and an Aboriginal right to religious practice under section 35 are jointly put forward, each provision must be considered separately. When Aboriginal groups negotiated for section 35 in 1982, they never once thought their Charter rights were going to be supplanted. Aboriginal groups have the same right to section 2a’s promise of religious freedom that every other Canadian has. As such, the Minister’s failure to consider section 2a was an error in law. The Appellants argued that the correct standard of review of the Minister’s decision is correctness, not reasonableness. The Minister had a Charter right addressed to him, and didn’t address it—therefore, the standard is not whether this decision was within the range of reasonable alternatives (the reasonableness standard), but rather whether it was the correct decision.

The Argument of the Respondents (Minister of Forests, Lands, & Natural Resources and Glacier Resorts)

There were three counsel for the respondents: Gregory Tucker for Glacier Resorts and Erin Christie and Jonathan Penner for the Minister of Forests, Lands, & Natural Resources.

The arguments by Glacier Resort focused on how the resort went to “extraordinary lengths and made many changes to the Resort plans” (page 1, factum) to accommodate the needs of the Ktunaxa, and, up until 2009, the Ktunaxa never indicated that their concerns couldn’t be adequately addressed.

Gregory Tucker for Glacier Resorts focused on two main factual issues in his submissions:

- That the resort did not proceed in the face of “constant and inveterate” opposition, as the Ktunaxa claim, but rather engaged in an ongoing conversation premised on accommodation and negotiation, which the resort thought was succeeding until 2009.

- It was not only the Ktunaxa’s position that changed in 2009, but also the nature of the belief. The chambers judge made detailed findings on this, determining that the Ktunaxa veto of overnight accommodation specifically was a belief of recent origins and was not held back during negotiations because of religious secrecy (i.e. that only elders held this religious knowledge), as the Ktunaxa claimed. Counsel noted that overnight human accommodation was key to this project since its proposal in 1991. If this aspect of their spiritual belief was core, why was it not raised much sooner?

Counsel for the Minister of Forests, Lands, & Natural Resources divided their submissions into those that focused on section 2a and those that focused on section 35.

Jonathan Penner argued that 2a was not engaged in the first instance in this case for the following reasons:

- No Charter right is absolute, including 2a, with most Charter rights having some internal limits.

- One of section 2a’s internal limits is that it does not protect religious rights that involve the coercion of others.

- A second internal limit should be that section 2a does not protect sacred sites, particularly when there is no legal right to a sacred site (the Ktunaxa do not have title to the land in question). The “sheer scope of possible conflict” in allowing sacred sites within 2a is too much.

- Statutory decision makers can make decisions that infringe on Charter rights, as long as they weigh the infringement against statutory objectives. Here, subjective meaning of religious belief has possible infinite value to claimant, so the Minister cannot meaningfully weigh or balance the opposing interests.

Counsel concluded by arguing that the appropriate standard of review is reasonableness—the Court is limited to the reasons expressed by the decision maker (the Minister) and whether those reasons are within a range of reasonable outcomes. It was reasonable for the Minister to determine that section 2a was not engaged in this case for the above reasons.

Erin Christie argued that Crown consultation under section 35 was adequate in this case. The asserted right under section 35 here was the right to “exercise spiritual practices which rely on a sacred site and require its protection” (factum, 31). Counsel argued that the difficulty with this asserted right was that it was framed in absolute terms, making it almost impossible for the Crown to accommodate. The Crown engaged in “deep consultation,” (p. 35 of factum) with the whole consultation process lasting decades. And yet, the Ktunaxa now say they cannot reconcile the Proposed Resort with their spiritual beliefs in any way. The duty to consult, Haida says, does not mean a duty to agree, and the consultation process does not “give Aboriginal groups a veto over what can be done with land” (Haida, para 48).

The Intervenors

There were fourteen interveners in this case. I have listed them below with links to the associated factums.

There were a number of common themes among the intervenors. Some argued about the scope of section 2a (that it should protect sacred sites [BCCLA] and communal religious rights [Evangelical Fellowship of Canada; Alberta Muslim Public Affairs Council]). Others argued for specific ways to weigh the proportionality analysis (that it should consider past colonial practices against Aboriginal religious freedom [BCCLA] or that it should consider the goals of reconciliation [Katzie FN, Canadian Muslim Lawyers Association]). Many of the Aboriginal groups argued about the sacred importance of land, and how that should be considered within the Charter [Katzie FN, Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance].

Meanwhile, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce argued that 2a should not protect religious beliefs that “restrain the otherwise lawful and competing behaviour of others that do not share the same religious beliefs” and further argued that, where section 2a and section 35 are both engaged, they should be considered together using a Doré analysis (the analysis done when a case involves applying the Charter to adjudicative decisions rather than legislative ones). The Attorney General of Saskatchewan argued that Aboriginal groups have reciprocal duties towards the Crown during consultation: they must not take unreasonable positions that frustrate reconciliation, and they must fully and clearly express their interests and concerns early in the consultation process.

The most powerful intervenor speech was that given by the lawyer from the Council of the Passamaquoddy Nation [at 01:32 of the webcast]. Speaking to the fact that the Ktunaxa were eventually unwilling to compromise in later negotiations, Paul Williams said:

“You have heard that Qat’muk has been logged, skied, hunted, and the Ktunaxa have not gone to court over these things. The Ktunaxa went to court when the government decided to take up the land in a way they could not accept. Court is confrontational, expensive, emotional, a last resort. But what you seem to be saying is: Canadian constitutional laws are about compromise and where is your compromise now? The Ktunaxa have compromised already. Sometimes there is no middle ground left.”

The other intervenors in this case were:

- Evangelical Fellowship of Canada

- British Columbia Civil Liberties Association

- Alberta Muslim Public Affairs Council

- Katzie First Nation

- Canadian Chamber of Commerce

- Attorney General of Canada

- Attorney General of Saskatchewan

- Te’Mexw Treaty Association

- Canadian Muslim Lawyers Association et al.

- Shibogama First Nations Council

- West Moberly First Nations et al.

- Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance

- Amnesty International Canada

- Council of the Passamaquoddy Nation at Schoodic

Moving Forward

Much of the judges’ questioning seemed to centre around a concern that the claims of the Ktunaxa could result in an ‘exclusive’ right to the land. The Ktunaxa had apparently expressed a willingness to be accommodated initially, went to the negotiating table with the resort company, and then firmly changed their mind to essentially veto the project. McLachlin CJ, Moldaver J, and Abella J all expressed concern about the fact that there was no middle ground for the Ktunaxa. Was the Ktunaxa religious claim even a sincere one, given the fact that they were willing to compromise at first, and then later said their religious beliefs would not let them accept any accommodations? How do we deal with a position that has no middle ground when weighing values in a proportionality analysis? And what happens under a section 35 analysis, where the government’s duty to consult and accommodate runs up against what amounts to an Aboriginal veto of the development?

I firmly maintain the stance that the Ktunaxa’s section 2a claim was infringed in this case. There is no apparent reason, such as coercion, that should limit this claim from the scope of 2a. As noted by Shibogama, the development is on Crown land, not private property. As Crown land, any government decision related to it is arguably subject to the Charter. As such, coercion of the developers doesn’t come into it. Further, if we don’t include sacred sites into section 2a, then we essentially exclude Aboriginal spirituality from the Charter. Any competing claims, like those of developers, should be considered under section 1, which is a much finer tool than the bluntness of excluding claims from the scope of 2a.

However, a more difficult barrier set before the appellants may be the precedent established in Doré, which clearly outlines that Charter decisions are reviewed on a reasonableness standard, not a correctness standard. The reasonableness analysis asks whether the decision “interferes with the relevant Charter guarantee no more than is necessary given the statutory objectives” (Doré, para 7). The judges showed interest in knowing how the Ktunaxa veto on the proposed project could be weighed at all under this reasonableness analysis. Counsel for the appellants pointed to the fact that many religious claims are framed in absolute terms—the Hutterian in Alberta v Hutterian Brethren didn’t just say, no colour photos for our driver’s licenses; they said, no photos, period. But administrative law principles did not arise in that case. It is clear that the courts were interested—and perhaps concerned—about how a proportionality analysis, pursuant to the framework set out in Doré, would be done in this case.

Another barrier to the appellant’s claim lies in section 35. The Ktunaxa’s ‘veto’ of the project, the fact that the spiritual concerns about overnight accommodation were perhaps of recent origin, the extensive consultations, and the fact that there is “no duty to agree” under section 35 could all prove difficult for the Ktunaxa in meeting the test under section 35.

To this point, there were a number of questions from the bench on how section 35 and section 2a should work together. Section 35 protects certain rights, like hunting, fishing, and practicing one’s culture, but only if they meet the Van der Peet test. The temporal element is crucial—only rights that existed pre-European contact are protected under section 35. The bench seemed concerned that the Ktunaxa’s spiritual beliefs were only recently asserted, meaning they would not meet the Van der Peet test. But Aboriginal groups in Canada are still protected under the Charter, like every Canadian. They are not “antiques preserved in amber from the pre-colonial past” (factum of Te’Mexw, page 1). The Ktunaxa beliefs could still meet the test for section 2a, which has no temporal element as a barrier, while not meeting the test for section 35. The factum of the Attorney General of Canada gives an excellent overview of how the two sections work, arguing that though the sections are complementary, they are not interchangeable. And the test under 2a is easier than 35. If the Ktunaxa’s claim fails under 35, which it may very well, I can only hope the court allows the claim within the scope of 2a, where it rightfully belongs. This would protect the current spiritual practices and beliefs held by current Aboriginal groups, though it still leaves the court with the difficult decision of whether the religious right can be limited by legitimate state objectives. It will be very interesting to see what our highest court decides.

Join the conversation