Google v Equustek: Courts Still Don’t Understand the Internet

On December 6th, 2016, the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) heard the case of Google v Equustek. The SCC is being tasked with defining the legal obligations of online intermediaries such as Google. In coming up with these definitions, the SCC must also answer difficult questions surrounding the regulation of illegality on the internet – a setting that is virtual, global, and controlled by conflicting domestic laws. Many entities intervened in support of Google, and many more filed to intervene. The Justices at the hearing, however, didn’t seem to be impressed with any of them. If the SCC upholds the British Columbia Court of Appeal decision against Google, the Court risks setting an international norm where local standards are applied to global conduct – effectively giving a single court or country veto power over Internet speech. That’s a big problem for everyone.

Factual Matrix

The proceeding dates back to 2011, when Equustek Solutions Inc. sued its distributor, Datalink Technologies. Equustek designed and manufactured industrial network interface hardware and sold it through Datalink, until Datalink unlawfully acquired Equustek’s confidential information and trademark secrets. Datalink then continued advertising Equustek’s products while shipping their own versions of the products to customers. Equustek obtained multiple injunctions to prohibit Datalink from carrying on their unlawful business. Datalink ignored all court orders, moved overseas, and continued their clandestine operations from several different websites.

In 2012, Equustek reached out to Google to block Datalink’s websites from appearing in Google search results. Google voluntarily blocked 345 individual web-pages from the Canadian Google site, but declined to block entire web domains from all international Google sites. Equustek took Google to the British Columbia Supreme Court (trial court) and obtained an injunction that required Google to scrub all of Datalink’s web domains from its global index – making the injunction, essentially, a global takedown order.

Google Appeals

Google appealed with three arguments:

- The British Columbia Supreme Court did not have the jurisdiction to obtain or enforce the injunction;

- The injunction was obtained improperly because Google was an innocent non-party to the litigation; and

- The injunction had an impermissible extra-territorial reach and effect.

The British Columbia Court of Appeal (“BCCA”) dismissed Google’s appeal. The BCCA found that the trial court had territorial competence over Google, as well as in personam jurisdiction, because Google did business in the province. It also found it was appropriate to seek relief against Google to give effect to the original injunctions that were ignored by Datalink. Finally, the BCCA held that the global takedown order did not violate principles of comity because Datalink’s breach of intellectual property laws was illegal in most countries, and it was not a matter of free speech. Google then appealed to the SCC.

What is Google, anyway?

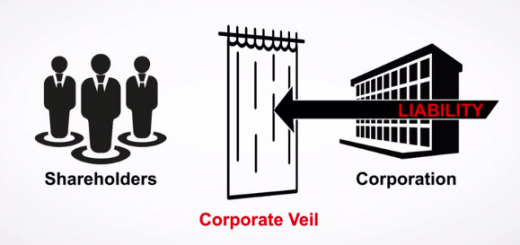

There is certainly a lot to unpack in this case, but I would like to begin with a discussion of in personam jurisdiction. The BCCA applied the “real and substantial connection” test from Club Resorts Ltd. v Van Breda to find that the trial court had jurisdiction not just over the subject matter (i.e. territorial competence) but actual jurisdiction over Google as a party. This gets to the foundational issue of what we believe the role of a search engine is, and whether that role is passive or active. Construed as passive intermediaries, search engines help internet users find content that they want to find. On the other hand, construed as active intermediaries, search engines lead internet users to find content, which users then review to find what they want to find. The distinction is not superficial.

The BCCA found that Google’s search results are generated using Google’s highly confidential proprietary algorithm. Google collects a wide range of user information to generate results such as user searches, IP addresses, locations, search terms, and user behavior (i.e. whether the user clicks through the search results generated) (para 23, 49). Google also links ads to the subject matter of the user’s search, as well as the user’s history and location (para 54). In a 2014 case of Google v Spain, the European Court of Justice found that Google was a “data controller,” and in this way, was an active intermediary. The BCCA seemed to agree here. Even though Google did not have resident employees, business offices, or servers in British Columbia, the BCCA found that the information which Google collects from British Columbia residents to generate results was a key part of their business model. This was sufficient to establish a real and substantial connection for in personam jurisdiction.

Absurd Results

If we accept the BCCA’s argument on its face, however, it leads to some absurd results. As the British House of Lords rightly pointed out in their report on Google v Spain: “If search engines are data controllers, so logically are users of search engines” (para 41). This reasoning also leads to yet another absurd result which Google pointed to in their factum: if Google’s user data collection ties Google to the users’ jurisdiction, then the civil courts of every country on earth could assert jurisdiction over Google. This raises the specter of Google being subjected to restrictive orders from courts in all parts of the world, each with their own domestic laws.

The BCCA did not engage with these questions at much length, opting instead to suggest Google was a victim of its own success. Mr. Justice Groberman of the BCCA agreed with the trial judge’s statement:

“I will address here Google’s submission that this analysis would give every state in the world jurisdiction over Google’s search services. That may be so. But if so, it flows as a natural consequence of Google doing business on a global scale, not from a flaw in the territorial competence analysis… Further, the territorial competence analysis would not give every state unlimited jurisdiction over Google; jurisdiction will be confined to issues closely associated with the forum in accordance with private international law.” (para 52)

I find this to be entirely unconvincing. First and foremost, by the line of argument that Google is a victim of its own global success, Equustek is also such a victim. By choosing to advertise and sell its product online to customers around the globe, Equustek should have to start proceedings in every jurisdiction that their product was bought and sold illegally. Surely, the BCCA would not find this course of action to be reasonable. In fact, when Google argued in the SCC hearing that an order should be obtained from each country where the offending Datalink site is hosted, Justice Abella questioned its reasonability.

Secondly, one of the key roles of the court is to interpret and apply laws. It is the court’s task to ensure a law evolves with the times and is augmented if need be to meet new social developments and to account for new challenges. If a law cannot account for the absurd result of a business being subjected to every state’s jurisdiction, the law is defective. If a court cannot correct this defect, it should not issue an order under a defective law.

Finally, while it may appear that jurisdiction was “confined to issues closely associated with the forum” (i.e. Google operations in British Columbia) in the case at bar, the injunction that flowed from the finding of jurisdiction was not closely tailored to the issues (i.e. ceasing the illegal actions against a British Columbian company in British Columbia). The trial court essentially drew borders on the internet to find that it had the jurisdiction to issue an injunction that is, in effect, borderless.

Dangerous Consequences

The enforcement of the injunction, which lacks any geographic and temporal limits, raises a few other concerns. The BCCA found that Google would not be inconvenienced in any material way by the order, and that Google would not incur expense in complying with the order. The BCCA, however, did not provide any guidance as to how Google should implement the order. While this can be viewed as BCCA exercising judicial restraint, the BCCA is effectively leaving it up to Google to craft the mechanism to find and take down Datalink’s illegal content from Google’s index. In crafting this mechanism, Google will undoubtedly be concerned about its future liability for hosting content that a court deems to be illegal. After all, the BCCA has laid the groundwork for Google to be subjected to restrictive orders in all jurisdictions within which it operates.

The first problem is that Google works with automatic algorithms, which makes it difficult to censor what is published in Google’s index and what is not. It is also very difficult to craft the means by which Google can become aware of illegal content – whether that conduct is illegal in most states (i.e. violating intellectual property rights like in the case at bar) or illegal in just one of the states where Google operates. It is therefore close to impossible to ensure all information that Google indexes complies with each country’s laws. In light of this, Google may need to set up monitoring systems, notice-and-takedown systems, or some other procedures to allow for rapid response to illegal content in order to avoid liability.

Both the monitoring and notice-and-takedown systems have been contemplated recently by the European Court of Human Rights in the cases of Delfi v Estonia and MTE v Hungary , respectively, and have faced significant criticism. In Europe, for example, internet service providers cannot be held liable for hosting illegal content – only users who upload the content are liable. The concern behind this policy is that internet providers might be forced to police the internet. This policing activity would force the providers to incur not only monetary costs, but it would have an immense chilling effect on free speech as providers would be incentivized to catch potentially illegal content as well as content reported to be illegal. This chilling effect is compounded by the fact that domestic laws around the world often conflict with one another. While it may be true that an order prohibiting Datalink from advertising wares that violate Equustek’s intellectual property rights will not offend the core values of any other nation, there is danger in looking at the order in the vacuum of the case. Hate speech may be “clearly illegal” in many countries, but the contours of what constitutes hate speech in any one country differ significantly worldwide.

In conclusion, the SCC is tasked with setting a new international norm. The pressure on the SCC is immense, but it must not go too far in upholding the rights of a private entity such a Equustek, and instead consider alternative, more tailored solutions. It must wrestle with the issues discussed, and not simply set them aside as the BCCA did with a statement that the global takedown order “can be varied” in the future. Failing to understand the broad consequences a global takedown order can have upon free speech, access to knowledge, and the internet at large – as many courts have failed to do in the recent past – will not only result in a national embarrassment, but deleterious, global effects for years to come.

Join the conversation