Section 24(2) of the Charter: A Legal Fiction?

In the mind of this Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982 [“Charter“] aficionado, the most significant recent development in Charter history is the Ontario Court of Appeal decision that effectively renders s. 24(2), the exclusion of unconstitutionally obtained evidence that could bring the administration of justice into disrepute provision, virtually non-existent. Just as a forenote to this discussion, let’s recall that in pre-Charter times, illegal or problematic actions by the police left victims of such actions with remedies only available in civil court. The way the Charter gave life to these fundamental rights and freedoms was by allowing the exclusion of evidence in criminal trials when it was obtained in manner that violated an individual’s constitutionals rights – and frankly besides exclusions there is no other real remedy.

For example, if an officer stops, questions, and searches a person solely on the basis of race – the person was simply walking to the bus stop doing nothing out of the ordinary – and were to find something illegal (a small amount of marijuana for personal use, for instance), how can we allow evidence obtained solely out of racism to be used against a person at his or her criminal trial? Anything short of excluding that evidence is not a real remedy.

The Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”) has defended the exclusion of evidence in R v Stillman, [1997] 1 SCR 607 [Stillman], however, the Ontario Court of Appeal (“ONCA”) has recently made a marked change in direction. In the recent cases of R v Grant, 2002 CanLII 41531 (ON CA) [Grant] and R v L.B., 2007 ONCA 596 (CanLII) [LB], the ONCA unanimously refused to exclude evidence obtained by grievous police conduct. Arguably the Court of Appeal is trying to reformulate the law set out in Stillman and it seems apparent that no matter what the police do to an accused, if a gun is involved, it will not be excluded from evidence in Ontario. Let’s consider the implications of this. If Charter rights are violated, the accused has no remedy for the fact that he was illegally searched, detained, or essentially tortured (tazered). It is fair then to say that these Charter rights do not legally exist.

How can we, with any intellectual honesty, believe that someone will not be arbitrarily detained if the police know that the fruits of that illegal detention will be admitted against the accused at trial? The Ontario Court of Appeal has sent a clear message to police that no matter what they do to persons, if they find a gun, the court will excuse the police misconduct and our Charter rights become, in a sense, mythical. Again the Ontario Court of Appeal this month in R v Harrison, 2008 ONCA 85 (CanLII) [Harrison], refused to exclude evidence under s. 24(2) despite unspeakable conduct by the police. There was, however, an excellent dissent by Justice Cronk who at least in recent s. 24(2) jurisprudence, appears to be the only judge at the court to defend and uphold the exclusionary remedy.

Two of these cases, Grant and LB, have been appealed to the SCC. The risk in these cases going to the SCC is that the Court can reverse direction on Stillman and essentially render s. 24(2) a mere fiction. Whereas had these cases not gone up, lower court judges, like Justice Ducharme of the Ontario Superior Court, could still utilize cases like R v Collins, [1987] 1 SCR 265 [Collins], and Stillman to exclude evidence.

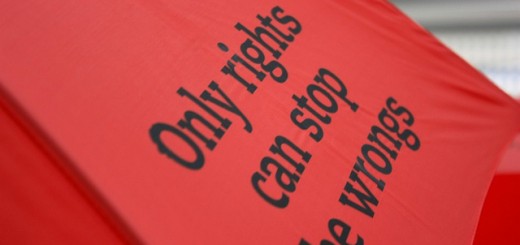

In the recent decision of R v Padavattan, 2007 CanLII 18137 (ON SC) [Padavattan], Justice Ducharme recognized that the Ontario Court of Appeal has recently tried to change the s. 24(2) rule and could have towed the line at Old Osgoode, but instead took a strong principled approach, maintaining that the SCC decision in Stillman should stand. Just as Justice Ducharme stood up for s. 24(2) in Padavattan, we should hope that the SCC stops this crime control hysteria and defends Canadians’ constitutional rights by giving life to the real operative exclusionary rule that we have in s.24(2) of the Charter. If they choose to abandon all notions of civil liberties and fundamental freedoms as the Ontario Court of Appeal fundamentally has, we will create a situation in this country, where we are allowing the police to engage in any conduct that essentially ignores the Charter and makes it meaningless. The Charter was written and exists to protect citizens and their fundamental liberties from intrusions from that state.

No arm of the government can intrude on an individual’s liberties more than the police; thus, it logically follows that they should be subjected to strict constitutional controls in order to protect our liberties. At the moment, at least in Ontario, it seems that the highest provincial court believes that the police should have no curbs on their actions when their goal is to get serious drugs or guns off the streets; let’s wait and see if the SCC feels the same way.

Join the conversation