March 8, 2010

The Supreme Court of Canada ("SCC") recently released official statistics on its work in 2009 along with comparisons with the previous ten years: Bulletin of Proceedings: Special Edition, Statistics 1999 to 2009 (26 February 2010). The official statistics are interesting and insightful. In light of recent, flavourful TheCourt.ca posts by my friend James Yap ("Judgment of the Decade," "the First Annual Ozzy Awards") I decided to add to the official statistics by compiling some judge-specific statistics of my own, included in the second half of this post.

Applications for Leave

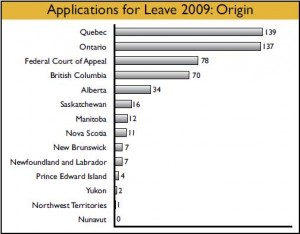

In 2009, 556 appeals were filed with the SCC, of which 542 were applications for leave to appeal and 14 were appeals as of right. 518 of these applications were considered by panels of the Court for decision (the remaining carry over to 2010). Not surprisingly, more than half the applications originated in either Quebec or Ontario (139 and 137, respectively).

Appeals Granted

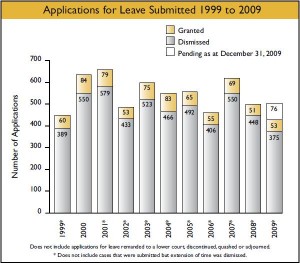

The 518 applications considered by the Court are roughly in line with the past 10 years (with the lowest being 458 in 1999 and the highest 668 in 2001). The Court has also maintained a roughly consistent proportion of appeals granted each year. In 2009, the Court granted a hearing in 53 appeals (10% of the applications). In 2001, where the Court considered the highest number of appeals, it granted a hearing in 79, representing 12% of the total.

The number of appeals granted (or number of appeals granted out of appeals filed) each year is an interesting trend. The proportion seems to be consistently within the 10-13% range regardless of the change in number of applications filed, indicating a possible policy preference to maintain consistency in the proportion (rather than the number) of appeals granted each year.

Although a roughly equal number of applications originated in 2009 in Ontario and Quebec, 22 of the 139 Quebec appeals were ultimately heard, while only 12 of the 137 Ontario appeals were heard. However, it would be premature to derive any conclusions from this. When the Supreme Court released similar statistics in 2007, BC was over-represented on the number of appeals heard with 13 of 105 being heard.

Judgments

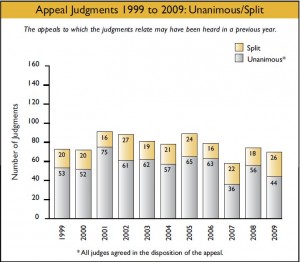

The Court rendereds 70 disposition in 2009, allowing 26 appeals while dismissing 44. The proportion of appeals allowed in 2009 was on the lower end compared to the decade as a whole. In 2008, the Court allowed 34 of 84 appeals while in 2006, the Court allowed 49 of 79 appeals, representing the highest proportion of appeals allowed in the decade. Only in 2001 (when 28 of 91 appeals were allowed) was there a lower proportion of successful appeals than 2009.

Of the 70 dispositions, 26 were split and 44 were unanimous. The high rate of split decisions was previously matched only in 2007, when 38% of the decisions were split. Besides 2009 and 2007, the trend in the past ten years has been between 20-30% split decisions.

Judgments: Unofficial Statistics

Although the official Supreme Court statistics are interesting, they are silent on data associated with each judge. To "spice up" this post on statistics, I decided to compile some data on decisions rendered in 2009 based on neutral citations (62 decisions from 2009 SCC 1 to 2009 SCC 62).

An obvious disclaimer is that one year's worth of data is too small a sample size to derive any conclusions. These findings highlight only the promise that a more comprehensive statistical project could provide.

Writing for the Majority

Of the 62 decisions rendered in 2009, only one, very brief decision was delivered by "The Court." The most prolific writers for the majority were Justices Lebel, Rothstein, and Chief Justice McLachlin, penning 9 judgments each. Justice Binnie penned 8 majority judgments; Justices Fish and Abella penned 8; Justice Charron penned 6; and Justice Deschamps penned 4. Understandably, Justice Cromwell, who joined the Court mid-session, penned only 2 majority decisions.

Dissenting

There were a total of 31 dissenting judgments in 2009 (some representing multiple dissents in the same case -- of the 62 cases decided, 23 had dissents). The most prolific dissenter was Justice Fish who dissented 9 times. On the other end of the spectrum, Chief Justice McLachlin and Justice Charron dissented only once each. In terms of length of dissent, Justice Deschamps was a clear leader with her 4 dissents totalling 279 paragraphs (or 69.8 paragraphs per dissent).

Most of Justice Fish's dissents were on criminal/constitutional matters although he also penned a notable dissent in the administrative law case of Khosa. Justice Deschamps' dissents were consistently detailed, regardless of the area of law. For example, she wrote a notable dissent in Caisse Populaire Desjardins de l'Est de Drummond, 2009 SCC 29, but also an equally exhaustive dissent in Marcotte v Longueuil, 2009 SCC 43.

Concurring

14 of the 62 judgments released in 2009 had concurring opinions, some with multiple concurring opinions. The total number of concurring opinions rendered was 19. Justice Deschamps had the highest number at 5. Justice Cromwell and Charron had no separate concurring opinions in 2009.

Profusion

Due substantially to the 203-paragraph judgment in Ermineskin Indian Band and Nation v Canada, 2009 SCC 9, Justice Rothstein was the most prolific judge overall in 2009, writing a total of 804 paragraphs in 12 decisions. Chief Justice McLachlin and Justice Deschamps also had a heavy writing load, penning a total of 699 paragraphs each in 12 and 13 total judgments respectively. Due to his 9 dissents, Justice Fish had the highest number of total judgments at 19, and wrote a total of 577 paragraphs. In a way, he was also the most concise writer, with approximately 30.4 paragraphs per judgment.

Assisted and Dissented From

The only judge who squeezed through 2009 without having to be lectured by one of his or her peers was Justice Cromwell, whose 2 majority opinions of 2009 were neither dissented from nor separately concurred with. Justices Abella and Rothstein stirred the highest level of dissent with their majority opinions. Of Justice Abella's 7 majority opinions, 4 attracted dissents, and of Justice Rothstein's 9 opinions, 5 attracted dissents. Justice LeBel also had 4 of his 9 opinions challenged by dissents.

In terms of separate concurring opinions, Justice Abella's 7 opinions were again accompanied by 4 separate concurring opinions by other judges. Although many of Justice Rothstein's opinions attracted dissents, his majority opinions had no concurring opinions. The Chief Justice did not get any higher level of deference from the other judges. 3 of her 9 opinions attracted dissents, and 2 included separate concurring opinions.

Conclusion

The above unofficial statistics are meant only to spur interest and curiosity into the personalities of the justices at Canada's top legal institution. Could a more in-depth statistical project, with a larger sample size, provide useful conclusions (akin, for example, to Benjamin Alarie and Andrew Green's project, or Donald Songer's Supreme Court of Canada: An Empirical Examination)?

The first step would be to establish whether there are statistically significant trends (derived, say, from a decade's worth of judgments, or from a retired judge's entire repertoire of judgments). Next, can qualitative conclusions be derived from such data? For example, instances where one justice consistently attracts dissents may represent that her or his unique understanding of the law, specialization in a specific area of the law, or the courage to take up difficult and challenging cases as the majority author. Instances where a judge's decisions are consistently accompanied by concurring opinions may again represent a unique approach to the law and reasoning for that individual judge.

Could the data be further extended to reflect interpersonal relationships, politics (in the small "p" bargaining sense), and team dynamics between the justices, independent of the content of the case being heard? The possibilities of such research are endless...

Graphics originally from the Supreme Court of Canada, but made without their endorsement. TheCourt.ca is in no way affiliated with the Supreme Court of Canada.