On Administrative Law and Braces: Shiner v Canada

Every so often, a legal dispute–not (yet) at the Supreme Court, but winding its way through the system–captures the attention of the Canadian public. When this happens, it is not because of the specific legal issue posed and addressed (although obviously this is a component), but because the specific facts of the case attract a coalition of issues important to Canadians.

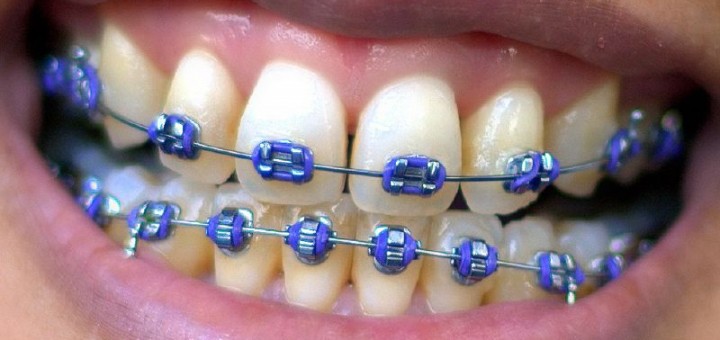

The problem with this trajectory, though, is that it can open a gap between the Twitter-worthy headline of the case and the legal doctrines applicable to the issue. These cases remind the legal community why law can’t happen in a vacuum and at the same time we start to question law’s priorities. Shiner v Canada (Attorney General) 2017 FC 515 [Shiner] is a paradigmatic example of this dynamic. Capturing the ire of many Canadians, the case is better known as when “Ottawa Rack[ed] up $110,000 in Legal Bills to Avoid Paying for Indigenous Teen’s Braces” (Toronto Star, Sept 29, 2017).

However, Justice Harrington characterizes the issue in a very different light. The decision begins with the following statement: “the one; the only; legal issue in this judicial review is whether the federal government should pay for Josey Willier’s dental braces.” (para 1). This isn’t a normative question; the court isn’t asking whether it is right for the government to pay for braces. Rather, the issue is a matter of administrative law: was the decision to deny the braces both procedurally fair and substantively reasonable?

In what follows, I will discuss both the facts and decision in Shiner in order to make some broader comments on the relationship between braces and administrative law; administrative law, Indigeneity and the welfare state; and why the government spends money on lawyers.

What Does the Federal Court Have to Say About Braces?

Like many teens, Josey needed braces. Unlike many others, before her braces Josey suffered from a “severe and handicapping malocclusion” (para 4) and, as a result, took daily pain medication to endure the resulting pain.

While the cost of braces aren’t covered under Alberta’s health plan, as a member of the Indigenous community Josey’s mother, Ms. Shiner, applied for coverage under the Federal Non-Insured Benefits Program. But Ms. Shiner’s initial application to Health Canada for coverage and her three internal appeals were all denied.

After exhausting the internal appeal procedures, Ms. Shiner applied for judicial review. While Health Canada’s internal decision-making process is based on internal guidelines, judicial review invokes administrative law principles. Here, Justice Harrington considered whether the third and final decision made by Mr. Doidge–Director General of the Non-Insured benefits program–was fair and reasonable. Ms. Shiner’s case claimed that the decision was substantively unreasonable, because Mr. Doidge limited his consideration to four bullet points of criteria and failed to account for all relevant factors. Such considerations, it was argued, include the best interests of the child and Josey’s equality rights as a member of a First Nation. On procedure, the Ms. Shiner argued that the process was unfair, since no Health Canada orthodontist physically examined Josey, but instead based their decision on medical documentation.

In concise reasons, Justice Harrington disposed of both grounds of appeal. He reviewed the statutory language and the consultation process and decided that Mr. Doidge’s decision was reasonable since Ms. Shiner was unable to rebut the presumption that he considered the entire record (para 24). Considerations like the best interest of the child and Josey’s identification as a member of a First Nations community were found to be irrelevant (para 31). Further, it is not for the court to decide whether Health Canada policy could better consider certain factors (such as prevention); concerns over policy should be addressed through a policymaker, such as Parliament or Health Canada.

Meanwhile, on the question of procedure, Justice Harrington found that the decision-making process was fair. He held that, absent evidence to the contrary, medical documents were a sufficient basis for Mr. Doidge to make his decision (para 33). Further, if applicants feel that the process requires a physical examination, they should request one sooner.

The decision ends with Justice Harrington disposing of an equality claim made under Section 15 of the Charter advanced by the intervener in the case. The First Nations Child and Family Caring Society had proposed that Josey’s membership in a First Nations community meant that the decision engaged s15 Charter rights that Health Canada’s decision failed to properly consider. However, Justice Harrington found is no equality breach, since the Non-Insured Health Benefits program should be considered a section 15(2) affirmative action program (para 36).

Since the decision was reasonable and fair, there were no grounds to quash Mr. Doidge’s decision and Josey’s braces will remain uncovered by Health Canada.

So Why Do We Care About Braces?

At first glance, it seems absurd to spend over $110,000 in legal fees over braces that would cost $6,000. Even after reading the decision, this still may seem outrageous. Yet just as the ‘one and only issue’ in this decision isn’t braces, the numbers are but one piece of the picture and can’t capture everything this case is about.

At its heart (or at least as characterized by the Federal Court), this is an administrative law case. As soon as we enter administrative law, focus shifts away from resources, identity, equality, and even pain. We want to know if the parties had an opportunity to present their case. We further ask if the decision-maker acted within their statutory authority, and if the decision was within a reasonable range of options. If all of these criteria are met, the application for judicial review is denied and the decision is upheld. On administrative law principles, this case was relatively easy and the outcome just.

This case demonstrates the tunneling effect legal analysis can have. In pursuit of precision and in application of a cogent test, law often loses context. The issues that the litigant brings to the table are important to them–their identities, histories, and medical conditions–and yet often they are irrelevant to the analysis. This is the dynamic in Shiner; it’s not that Justice Harrington lacks empathy (see para 2). Rather, framing the case as a question of reasonableness and fairness these factors are prioritized while others move to the periphery.

One of those contextual issues forced to the sidelines is Indigeneity, reconciliation, and its impact (if any) for decision-makers. While identity played a role in the arguments, its significance in the judgement is largely rejected or ignored. The judgement seems to draw a line between historical experience and colonialism and current issues facing First Nations communities where the former is irrelevant. Paragraph 27 states, “with the greatest respect, this case has nothing to do with the European settlement of North America…with residential schools…with ‘scooping’ First Nations children from their homes.”

I question whether it is possible to say that this case has “nothing to do” with history. While I agree that the connection between colonization and braces isn’t as direct as it would be in a treaty rights case, history’s fingerprints are all over the policy directives we have today – from reconciliation to health care. Justice Harrington rejects the s.15 argument, that the decision should have accounted for equality concerns, because the benefits program could be considered an affirmative action program. But why should the nature of a program as one whose objective is to promote equality negate the need to consider equality concerns in the decision-making process? If anything, the nature of the policy as a 15(2) program should inform the decision. Rejecting the relevance of European colonialism allows the court to ignore the inequality and poverty effecting First Nations communities today. It devalues the perspective and expectations litigants bring to the courtroom. Worse, equality can’t be achieved through program objectives alone. If welfare objectives are not considered at the individual decision-making level, how can they be achieved?

And now we return to the money. The media conversation around this case has focussed mainly on how much the government spent on fighting Ms. Shiner. It is now clear that $110,000 wasn’t spent to fight an Indigenous teen, but rather to defend the decision-making process. Nevertheless, the headlines show the disconnect between administrative law principles and lived experiences of executive decision making. While the law has developed around notions of fairness and reasonableness, this decision shows how a narrow focus may skew the decision so it ignores other factors. There are two quotes from the judgment that are particularly powerful in this respect. In describing the community support allowing Josey to be fitted with braces, Justice Harrington writes,, “Josey doesn’t hurt anymore.” (para 2). Later, in finding the Health Canada decision was reasonable, he writes at para 31, “there is nothing to suggest that she was treated any differently than any other Canadian.” Is there a way to bridge the divergent notions of justice and proper outcomes in this case? I would hope that there is.

Perhaps courts and executive decision-makers widen the scope of what is considered reasonable or fair to include contextual factors outside of the direct issue at play. Or, maybe equality rights jurisprudence could have played more of a role in informing the content of a reasonable decision. Although this adds extra layers of complexity, and the decision still may be the same, a common vocabulary begins to grow. If we can agree that it is good that “Josey doesn’t hurt anymore”, then hopefully we can build a positive legal infrastructure to better achieve that objective.

Join the conversation