Heritage Capital Corp v Equitable Trust: Municipal compensation payments will not run with the Land

This guest post was contributed by James Steele. James Steele practices insurance, municipal, and commercial litigation with Robertson Stromberg LLP in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

- Absent express statutory language, positive covenants in favour of developers will not run with the land; and

- As incentive payments consequently constitute merely a contractual right, any assignment to a purchaser must occur by express wording in the sale documents.

Covenants under Municipal Heritage Statutes:

Provincial legislation empowers municipalities to designate heritage sites. As part of such designations, an owner and a municipality may enter into positive covenants in favour of the other. The owner may promise to rehabilitate or maintain the land. The municipality may in turn promise corresponding compensation payments to the owner.

But how can governments enforce such covenants in their favour? After all, the common law dictates that for a covenant to run with land:

- It must be negative in substance, and

- There must be both a dominant and servient tenement.

To address this, heritage property statutes abrogate common law requirements, permitting positive covenants to run with the land in certain circumstances. It was against this backdrop that the Supreme Court in Heritage Capital was asked to determine the full scope of such an exception in relation to the common law requirements.

Facts:

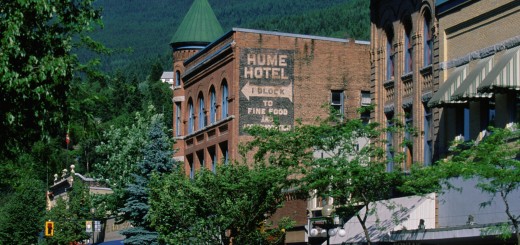

Predating the First World War, the Lougheed Building has long been a fixture of downtown Calgary. In 2004, the building was designated a “Municipal Historical Resource” under the Alberta Historical Resources Act, RSA 2000, c. H-9 (“HRA”).

In recognition of the rehabilitation burdens placed upon the owner, Lougheed Block Inc. (“Lougheed”), the City of Calgary agreed to compensation through annual payments (the “Incentive Agreement”). The agreement was registered to title. Lougheed later obtained financing from the Equitable Trust Company, and subsequently, Heritage Capital Corporation. At both times, Lougheed assigned its right to the Incentive Agreement as security.

Lougheed later defaulted, and a judicial sale of the building to 604 1st Street S.W. Inc. (the “Purchaser”) ultimately took place. When the Purchaser claimed entitlement to the remainder of the payments from Calgary, Lougheed applied for a declaration that:

- The Incentive Agreement was not an interest in the land; and

- The Incentive Agreement had not been included in the assets being sold to the Purchaser.

The master in chambers and the chambers judge both granted the declaration. A majority of the Court of Appeal held otherwise however, concluding that the HRA had set aside common law restrictions prohibiting the Incentive Agreement from running with the land. As such, it bound future owners.

The Supreme Court:

In their opinion, Justices Gascon and Côté confronted the following basic issues:

1. As a matter of property law, did the incentive agreement constitute a positive covenant running with land?

At common law positive covenants do not “run” with the land and therefore will not bind future owners. However, the Purchaser argued that s. 29 of the HRA provided a complete exception in the case of heritage property covenants. Section 29 reads:

29(1) A condition or covenant, relating to the preservation or restoration of any land or building, entered into by the owner of land and (a) the Minister, (b) the council of the municipality in which the land is located, (c) the Foundation, or (d) an historical organization that is approved by the Minister, may be registered with the Registrar of Land Titles.

…

(3) A condition or covenant registered under subsection (2) runs with the land and the person or organization under subsection (1) that entered into the condition or covenant with the owner may enforce it whether it is positive or negative in nature and notwithstanding that the person or organization does not have an interest in any land that would be accommodated or benefited by the condition or covenant.

[emphasis added].

Emphasizing that statutory exceptions to a common law principle should be narrowly construed, the Court held that s. 29(3) provided that only positive covenants in favour of the entities listed in s. 29(1) could run with the land.

Further, a contextual analysis of the HRA found that no broader interpretation was compelled by necessary implication. The purpose of s. 29 was intended to permit governments and public interest bodies to enforce covenants in their favour, despite having no interest in the land or building to which the covenant applied. Had the legislature intended to completely displace the common law by creating positive conditions enforceable by all parties, it would have said so expressly.

Ironically, the Supreme Court went on to determine that this particular Incentive Agreement showed no intention to run with the land in the first place. Rather, the payments were simply intended to go to Lougheed alone. Therefore, even if s. 29 had operated as the Purchaser argued, its claim to the payments would still fail.

2. As a matter of contractual interpretation, had the incentive agreement been conveyed by Lougheed as asset in judicial sale?

As any right to the incentive payments was merely contractual, did the Purchaser acquire such right through the judicial sale?

Heritage Capital is one of the first occasions in which the Supreme Court has applied its seminal 2014 decision in Sattva Capital Corp. v. Creston Moly Corp., 2014 SCC 53. That opinion affirmed that issues of mixed fact and law justified the application of the palpable and overriding error standard to contractual interpretation.

In Heritage Capital, the Supreme Court determined that the Incentive Agreement had not been included in the judicial sale. First, the description of the property being purchased merely described the Lougheed Building. Second, while the offer stated that all “leases and contracts that are assignable shall be assigned to the Purchaser as of the Closing Date,” such wording simply referred to contracts ancillary to the real property itself. It did not expand the scope of the “Property” being acquired.

In short, if the Purchaser had intended to also purchase the Incentive Agreement, its offer should have defined the incentive payments as among the assets included in the sale.

Lessons for Purchasers:

The implications of Heritage Capital are of national significance, as many Canadian provinces possess legislation providing for similar covenants over heritage sites.

By its decision, the Supreme Court has confirmed that (absent explicit statutory wording) only heritage covenants in favour of public bodies will run with the land. As such, purchasers of a historic property should expressly address this chose in action when describing the property to be transferred.

Join the conversation